Once is Never: Reconsidering Our Perceptions Of Failure And Success with Pulitzer Prize Winner Anthony Doerr

Failure has almost always never felt good, nor does it feel a path to success. When we find ourselves exactly in that moment, we immediately believe for it to be terrible. In this funny, poignant, and comforting talk by Pulitzer Prize Winner, Anthony Doerr, he speaks of the different perceptions and experiences of failure and successes that rings familiar to each of us—from great novelists and writers, to his own personal story. He brings out the kind of struggles that writers often feel, reframing it back to how we take failure on a daily basis and how we understand success. What kind of success should we chase after? How do we come to terms with failure? All of this as he reminds us how failing once does not count so much, that once is never—“einmal ist keinmal”.

—

Listen to the podcast here:

Once is Never: Reconsidering Our Perceptions Of Failure And Success with Pulitzer Prize Winner Anthony Doerr

This is the full presentation of Tony Doerr’s talk titled, Once is Never: Reconsidering Our Perceptions of Failure and Success from the 2018 Coca-Cola CMO Summit.

This is called Once is Never: Reconsidering Our Perceptions of Failure and Success. My mother was the type of mother who made her own peanut butter, baked the wheat bread she put it on and grew the alfalfa sprouts she put on top. Every morning when we were kids, my older brothers and I would file downstairs and swallow one spoonful of wheat germ and one spoonful of cod liver oil and then eat oatmeal our mother made for us. We then walked to the bus stop wearing mittens our mother made for us. If mom could have built the diesel Volkswagen she drove us around in, she would have. When this month came around, believe me, we were not permitted to purchase our Halloween costumes from a store.

Indeed, to attach the adjective store-bought to the noun costume to my mom was to indicate a certain area of indolence and underachievement and perhaps even a faint suggestion of bad parenting. As in old Marty Mortensen, he’ll probably be a store-bought superman. After all as the mythical life of Marty Mortensen demonstrated perfectly, there existed in our town certain parents who actually took their children to the royal-sounding restaurants on Mayfield Road known as Burger King and Dairy Queen. Establishments are known only to the Doerr boys as magical Shangri-La’s full of blissful children playing with insanely desirable toys that we whisked past on our way to school, our lunch boxes stocked with home-baked pumpernickel and heirloom carrots.

Halloween Costume Contest Of 1979

When I was seven, we received an invitation to an after trick-or-treating neighborhood Halloween party at David Petronzio’s house. The party our invitation proclaimed would culminate in a costume judging contest. The word up and down Shadow Hill trail was that the winners would receive trophies. My mom drove me to the Bainbridge Public Library, which was what mom did when confronted with pretty much any challenge. I selected a book titled Super Simple Creative Costumes. The costumes inside I was to learn later were neither super nor simple.

All the Light We Cannot See

After paging through the book for five minutes, I decided that I would win the biggest trophy by dressing myself as a knight in armor. I brought the book home, the costume in question featured a drawing of a dashing kid in full plate mail plumed helmet tucked under one arm, his jousting steed and stone keep sketched into the background. The instructions prescribed that the armor be made of 21 separate pieces of poster board covered with aluminum foil and held together with 300 little brass rivets. Mom drove me to drug mart, a destination second only to the library and its usefulness to the Doerr family. I decided I wanted to be a scary knight, a badass Sir Galahad. I picked up a black poster board. They only had nine sheets of black poster board at drug mart. I bought twelve white sheets too and spent two successive nights coloring them in with black markers.

Perception is selective. Click To TweetI worked for two weeks on this costume. The breastplate, the cuffs, the leggings, I fashioned the sword out of aluminum foil and a wrapping paper tube. I even created a shield with flames drawn on it, which wasn’t in the Super Simple Creative Costumes book but seemed essential. On the night before Halloween, it became time to make my helmet. In the book’s drawings, the princely cartoon boy wore a medieval headpiece with a chin guard and a working visor and an ostrich feather plume fixed jauntily to the top. Even now, years later, if I were to travel to Japan and train with an origami master for thirteen years, I would still not possess the skill to construct that helmet. Later that evening, I decided to execute my own design looping the poster board into a cylinder, gashing some mismatched eye holes in the front with an X-Acto knife and gluing the whole thing shut.

When Halloween night came, and I put on my suit of poster board armor, I could barely walk or see. If I’d been able to see myself from the outside, I would have seen a child executioner in ski gloves, the paper trash can on his head, a wilting black poster in one hand and a giant silver phallus in the other. When I was seven, I was interested in mirrors. In my mind, I was cloaked in armor, I was invincible. I was the black knight except that by the third house that Halloween it started to rain and soon the glue on my helmet gave way and my shield drooped and the magic marker on the white poster board started to bleed.

One of my casts sloughed off and we lived in the country where the houses were a good eighth of a mile apart. By the time I limped up David Petronzio’s driveway with my tattered shield and soggy milk duds, I had a little more than a mushy mass of black pulp piled up over my shoulders and a purplish magic marker stain seeping through my white thermal long underwear. Inside as you might imagine there were Batman and Darth Vaders and Incredible Hulk and Princess Leias parading around. There was even an Ichabod Crane with a real pumpkin on his head and everyone looked like who they had dressed up to be.

In the garage, three trophies were arranged on a card table, tall blue ones with a golden baseball player on top. Mrs. Petronzio gave out the awards and Ichabod Crane got first place and Wonder Woman took second. I don’t remember who got third. Needless to say, this was still a decade before the noun child got paired beside the noun self-esteem in the parlance of working-class Caucasian parents. I did not take home a trophy that night, but I did win a prize and it was for a category that some commiserative mom, perhaps Mrs. Petronzio herself, upon seeing me humped in the corner must have improvised on the spot. That category was titled most original. When she announced that at the end of the contest, the kids were no longer paying attention and I stepped shakily forward. Since there were no trophies left to give out, one of the dads clapped me on my soggy back then I walked home in the rain. I was seven and had no idea what original meant. My mom tried to explain it to me, unusual, different, inventive but I said, “My costume was terrible.” She said, “Your costume was not terrible.” I said, “It was the worst one by far.” She said, “It was beautiful.”

Once is Never: Readers have changed things, as no one can no longer immediately discern what someone reads by simply glancing the cover.

Writers On Writing

Here is from the German novelist Thomas Mann, “A writer is someone for whom writing is harder than for other people.” Here’s from the Austrian novelist Thomas Bernhard, “Whatever you write, it’s always a catastrophe. That’s the depressing thing about the fate of a writer. All you deliver as a bad ridiculous copy of what you had imagined.” Here’s from the French novelist Gustave Flaubert, “I am irritated by my own writing. I am like a violinist whose ear is true but whose fingers refuse to reproduce precisely the sounds he hears within.” The American poet, Randall Jarrell, once defined a novel as a prose narrative of some length with something wrong with it. Dana Spiotta, a living American novelist once told me, “For a novel to be successful, there has to be something failed inside it.”

A suicidal Virginia Woolf grappling to revise her last novel between the acts convinced herself that it was a failure. Herman Melville famously referred to his books as botches. The word Michel de Montaigne famous essayist chose to describe his prose ruminations in 1580 was essays, which at the time merely meant attempts, which suggested that he was fully aware of the possibility that they failed to achieve what he had hoped. As the writer, Zadie Smith, points out in this great essay called Feel Free is perhaps the most common writerly feeling. Upon rereading your work is T.S. Eliot’s Prufrock’s, that is not it, at all. That is not what I meant at all.

Worrying About Writing

Years ago, I published my fifth book, a novel set during World War II constructed from two braided narratives took me ten years of work, three trips to Europe and many afternoons of doubt. During the last push to complete the manuscript, I worked long days imprisoning myself in a desk chair for nine or ten-hour stints. With only a single break to walk to Albertsons supermarket to stare dazedly at the produce for a while like a caveman before purchasing a chocolate donut and eating it mindlessly while I walked back to my office. One November day, I spent a whole afternoon reworking a three-sentence paragraph that had given me fits for years wrestling with the following moment. A twelve-year-old girl who is blind who sits with her father in a train station in Paris, this is in June of 1940 as the German armies are entering the city.

Success is something that eventually comes to those who fail first and fail repeatedly. Click To TweetI have written, “Suitcases clang in and out of what might be doorways and trunks slide across tiles. Babies cry and little dogs yap and a conductor’s whistle blows and some big machinery coughs to a start and then dies. Sweat prickles the top of Marie’s scalp. She waits on the thin rim of whatever she’s sitting on and breathes and tries to calm her stomach. She tries to gather the city in her imagination. Cars throng down the avenues, a military ambulance careening past, hundreds of wet umbrellas pressed against the station gates.” After months of looking at photographs, years of considering and reconsidering this character, I reached the point where I could see this scene quite clearly hanging on the screen of my imagination as majestically and menacingly as I once saw this.

The Germans were on the edge of the city, but few Parisians had actually seen them yet. Some still refuse to believe the invasion was real while others were already fleeing, while still others wanted desperately to flee but could not because they had babies or jobs or elderly parents to care for or were disabled themselves. That November day, when I went back and reread the ham-fisted language I used to evoke that moment, I didn’t particularly approve any of it, “Suitcases clang or do suitcases clang or do they rattle or bang or clatter or clunk?”

If I’m going to take my book seriously, shouldn’t I search eBay from 1930s French suitcases, buy one, jam it full of antique clothes, run to a train station and see what sorts of sounds it makes. Also, were there even doorways and Austerlitz station in 1940? Were there tiles on the floors? Did conductors carry whistles in 1940? Were they even called conductors? Maybe they were brakemen or stewards or coach attendants. What if all the normal train employees had been sent to the front that day and what if this was an event that any proper and legitimate historian would know immediately? The infamous Parisian train employed draft of 1940. What if I’m the only idiot who doesn’t know about this event because I’m a doughnut-eating lunkhead sitting in a basement in Idaho making this stuff up? After about an hour or so of tinkering, I decided on the most prudent kind of revision, I cut the whole first sentence. Lawrence, a great New Yorker journalist calls this literary liposuction.

Unto that second sentence, seven simple words but containing enough failures to give me nightmares for a week, “Sweat prickles the top of Marie’s scalp.” According to my Webster’s New International, prickle means to prick slightly as with prickles or to cover with pricks or dots. Is that a proper evocation of what might be happening to Marie? Do I want my reader to imagine a bald girl with a welt covered scalp? Do I want to use a verb that sounds so much like pickle? Will the reader subconsciously think of her scalp being preserved in vinegar and brine? Is the top really where sweat comes out of a person’s head? Doesn’t it come out on the cheeks or around the neck? I don’t I remember sweating at some point during junior high from my earlobes. After spending a half hour on WebMD.com trying to figure out where sweat glands are located in the human head, I came to my senses and decided that I’ll just cut that sentence too.

Then there’s the third sentence that is a linguistic garden of fail, “She waits on the thin rim of whatever she’s sitting on. Breathes and tries to calm her stomach and tries to gather the city in her imagination. Cars throng on the avenues, a military ambulance careening past, hundreds of wet umbrellas pressed against the station gates.” Do I need to repeat the verb thrice? How would Marie know that the sirens belonged to a military ambulance? Do the sirens of military ambulances indeed have a different pitch? Were there even military ambulances in the city on that June day? Why wouldn’t all of them have been at the front? Did I make that up or did I see one in a photograph? Why do I have a distinct memory of seeing a photograph of a white Ford ambulance with a blue cross on it? Shouldn’t I have footnoted that in an earlier draft somewhere? Isn’t that what a proper historical novelist someone like Hilary Mantel would have done? Did it ranger in the evacuation? I think it did. Didn’t I read about umbrellas somewhere? I should probably dig up meteorological records from that date or maybe I could just say it was raining even if it wasn’t. Isn’t that what they mean by the dramatic license? If Hollywood can put Tom Cruise as a white guy Samurai teaching Japanese warriors how to use rifles 40 years after Japanese warriors were using rifles, I could surely let it rain the day Paris was invaded by the Germans.

If we rely on extrinsic yardsticks to measure our success, then we are not setting ourselves up to be our best. Click To TweetThen a line from a Paris review interview with Hilary Mantel flashes in front of my eyes, “Would you ever change a fact to heighten the drama?” “I would never do that.” Damn you, Hilary Mantel. Off I go Googling rain in Paris June 14, 1940 and click through a dozen photographs hunting for umbrellas and then I stop and think, “Why for crying out loud am I letting my narrator employ so many visual images in the second half of a paragraph in which the point of view character is blind?” That afternoon, I worked on this one paragraph for over two hours and whittled the whole thing down to a single clause, “Marie tries to calm her nerves, watched the three-minute video of lemurs eating strawberries and cream,” and reconciled myself to yet another provisional failure.

Then I decided that exercise might clear my head. I jogged over to the Boise YMCA and climbed onto a stationary bicycle and after pedaling along for a few minutes, a woman climbed aboard the bike besides mine. She put on some headphones and switched on a little Kindle. eReaders have changed things. You can no longer immediately discern what someone is reading simply by glancing at the cover. You have to do a little snooping. The woman was maybe 55 wearing a bright tank top and dark eye makeup and her black hair was guarded back into a ponytail, beaded bracelets jog up and down on her wrists and shorts. She seemed a very well-put together person. We pedaled a few minutes side by side and she turned pages with one finger stroking them out of the way rather eagerly I thought, and I began to steal glances. Would she be reading some Anne Carson or Alice Munro, Wallace Stegner or Ann Patchett? Maybe if I was very lucky there would be some Virginia Woolf on there and a few of Woolf’s dazzling sentences could filter into my head while I pedaled and helped me improve my wreck of a novel. Over her shoulder, I began to read.

Reaching forward, “Christian trails the tip of the crop from my forehead down the length of my nose so I can smell the leather and over my parted panting lips.” The first thought I had was, “What kind of crop? Corn?” The second was do lips pant? Isn’t it more accurately a mouth that pants or maybe it’s our entire respiratory system that pants? The third was how does a first-person narrator know why Christian is trailing the crop? The fourth was I think I know what book this is. My bicycling neighbor swiped pages hungrily the next dozen sentences I refuse to repeat to you here. “Finally, she got too abruptly, I wake gasping for breath covered in sweat and feeling the aftershocks of my orgasm. I’m completely disoriented. What just happened? I’m in my bedroom alone. How? Why? I sit bolt upright shocked.”

Like every other person in the English-speaking world, I’ve heard of the novel she was reading of course but it thus far cut me from experiencing any of its sentences. Here I was spending 50 hours a week trying to eradicate all the phrases in my novel that sounded like sweat prickles the top of Marie’s scalp. I was spending 100 painful minutes that very afternoon trying to understand what it feels like to be a young girl sweating in a Parisian train station, listening to the fulcrum of world history pivot. Here was a first-time novelist named E.L. James, writing a sentence like, “I sit bolt upright shocked.” Apparently spending no effort at all trying to decouple upright from its tenacious clinging boyfriend bolt and selling approximately six gazillion copies every week.

Once is Never: Most books that are truly original, that try to invent a new kind of grammar, entirely hover at the edges of the culture for years before they are either championed by someone influential or vanished.

As I pedaled away on my bike and my neighbor pedaled away on hers, both of us working up sweats presumably for different reasons. I had a miniature existential crisis. Why I wondered could E.L. James get away with letting a character gasp for breath when she doesn’t need the two words for breath since what we gasp for when we gasp is most clearly breath. Why would I spend an hour trying to come up with a new way to describe a sweaty scalp when it might reach a lot more readers if I just introduced a riding crop and the adjective panting? The answers it turns out had everything to do with my mother and that suit of armor I wore home in the rain.

Writing Conventions And Clichés

This is a letter to the magazine New Scientist from May of 1999. This guy wrote, “You report that reversing 50-millisecond segments of recorded sound does not greatly affect the listener’s ability to understand speech. Basically, inside a word if you flip the recording inside a longer word like hospital. He flipped inside of the recording and people can still understand it. This guy says, “This reminds me of my PhD in Nottingham University which showed that randomizing letters in the middle of words had little or no effect on the ability of skilled readers to understand the text. Indeed, one rapid reader noticed only four or five errors in A4 page of muddled text.” Why do you think he could read those letters so perfectly? I know this because he is an experienced skilled reader. He is seeing words like letters or keeping so many times in his life that his brain can automatically recognize them. He doesn’t have to parse each individual letter. He recognizes them in context in the pattern and just keeps going. Their patters are so familiar to him he doesn’t need to parse them. He doesn’t need to read each individual letter and he recognizes them as a whole and moves on.

You ought to chase your dreams simply as a way to allow yourself to play as well as you can. Click To TweetI’m going to give you a different example. Why do so many of us especially those of us who grew up in English-speaking households have a hard time counting Fs? Our brain is on autopilot. We’re habitual to so many things. When we read words on a page especially workaday propositions, like of or two or four, simple combinations of letters that we’ve seen thousands of times, we automatically slip into comfortable recognizable patterns, so we don’t have to pay as much attention. Perception is selective. We’ve seen the word of so many times it dims out of our consciousness and we don’t even see it anymore. The eye glides and the brain makes assumptions.

Clichés are simply bundles of words that have been grouped together so often that they’ve become as familiar to us as the pairing of the letters O and F. Convention has solidified certain packets of words into linguistic blocks that we plug into sentences like they were single units. In its original sense, cliché might have indicated a readymade unit of type. That’s what the word might have originally meant. A metal plate which issued on ending standardizes reproductions of print in the era of manual typesetting. Something like gasping for breath, for example, could have been an actual fixed block of time that a typesetter could plug into a sentence just like bolt upright or a chill ran up my spine or covered in sweat or crack of dawn.

The trouble with clichés is that because of their repeated use, they gradually become invisible to us. Clichés don’t ask us to see exactly what makes an eye glint or what’s so clear about a crystal or what it feels like to rear up in bed after some kind of sadomasochistic orgasmic dream. As writers, we might unwittingly pluck a cliché here and there from our memories because we’re in a rush. We tell ourselves we’ll fix it later because we’re being lazy some under rested Tuesday. We choose them both at the sentence and at the narrative levels because we’re afraid of becoming obtuse. We are afraid to divorce sweat from its stubborn predicate prickle. We are afraid to fail. We don’t have the will or the time or the courage and the skill to invent a new grammar, so we use the grammar people who have gone before us have used.

When I commit little failures like this, when I scramble to employ the clumsy symbols of language to try to articulate these things that are ultimately beyond language, who exactly am I failing? Until 1869 when this guy Leo Tolstoy published War and Peace in the world of literature was typically presented as splendid and spectacular. Military histories presented panoramas of glory and grandeur, but Tolstoy wanted to write a new kind of history. One that blurred fiction and reality, objectivity and subjectivity. He wanted to take the clichés of war and show his reader there are constituting units to take the familiar and store-bought values. Things like glory, heroism and honor. Things as familiar to his contemporary Russian readers as the word of is to us and to borrow the critic, James Woods image, he wanted to flip the Marshall tapestry around to reveal the unsightly tufts of threads on the other side.

Thirty-three years later, this guy James Joyce, he was a medical school dropout walking the streets of Paris. He was scribbling what he called epiphanies into a notebook, little jottings of overheard conversations or fleeting observations. Joyce was frustrated by the tropes, the systems of popular fiction. These are like chivalric romances, short stories that required a set of coincidences or contrivances to generate their plots. He found those things, those artifices unacceptably crude and he wanted to grasp toward something new or something he believed was truer. He began transforming those little notebook epiphanies into short stories with different kinds of structures. Stories that reached toward concluding moments in which he felt, “The soul of the commonest object who leaps to us from the vestment of its appearance and becomes radiant.”

In a sense, he wanted us to see those little Fs that have become invisible to us through habitualization. The structures of the short stories that this guy was writing were so unfamiliar to readers in the second decade of the twentieth century that his first story collection Dubliners was rejected 22 times over the course of nine years. It sold only 379 copies in its first year of publication and 120 of those were to Joyce himself. Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita was rejected four times by American publishers before a French publisher approved and willing to take a chance on it. Gertrude Stein submitted poems to magazines for 22 years before having one published. A Wrinkle in Time was rejected 26 times before it was published. Gone with the Wind was rejected 38 times. JK Rowling’s first Harry Potter novel was turned down twelve times before Bloomsbury took a chance on it. William Faulkner’s first novel, Sanctuary, was called unpublishable. Jorge Luis Borges whose work was initially deemed untranslatable and Marcel Proust after the third rejection for Remembrance of Things Past decided he would have to finance the publication himself.

It’s okay to accept failure; that language is only an arbitrary system of semblances and symbols. Click To TweetUnfortunately, there are very few commiserative moms in-charge of the marketplace ready to hand out trophies for most original. Most books that are truly original that try to invent a new kind of grammar entirely hover at the edges of the culture for years before they either championed by someone influential or they vanish. Among many minor failures, at least one large-scale failure lurks in this presentation so far. Pretty much all of my aforementioned examples, Thomas Mann, Thomas Bernhard, Virginia Woolf, Nabokov, Tolstoy, Joyce, JK Rowling, Proust, besides being Caucasian and many of them male, suggest that success is something that eventually comes to those who first fail and fail repeatedly That the most assiduous, tenacious and lucky among us are the people with the most grit perhaps, can manage to fashion their failures into rungs sturdy enough to carry them out of the flames of their mistakes. Into the glorious sun-drenched meadows of accolades and applause and adulation.

Writers On Success

Worse, the insinuation in my previous sections could be that this success is something we should all be striving for. This fallacy is so insidious that it lives inside our very language. In my Thesaurus, believe it or not, the words success is matched amongst other groaners to bestseller megahit, winner, big name, superstar and shiver celebrity. To succeed is to be desired. To succeed is to be celebrated. To succeed is to sell. Is that the sort of success we and our kids should always be chasing? An equation that correlates higher levels of commercial success with higher levels of happiness suggests a graph that I’ve almost never seen come true in real life.

Did selling lots of paintings make Mark Rothko happy? Did selling lots of albums make Kurt Cobain happy? Did selling lots of books make Hemingway happy? If we rely on extrinsic yardsticks to measure our success, if we count how many promotions we’ve won, how many followers we have or how many sites visits we got. How many people showed up to our inauguration, are we setting ourselves up to be our best selves? What I’m getting around to proposing is a different kind of question. What if it sometimes might be desirable to try something just to try it? Not to try it for the sake of a later distant but inexorable success, but just to try it for the sake of trying it, for the sake of dreaming and for the sake of the journey itself.

What I’m proposing is that if you want to write, maybe you ought to fashion these things out of tricky and unreliable entities called words just as a kind of play. If you want to paint, maybe you ought to put color on a canvas as a kind of play. If you want to make a movie or choreograph a dance or learn a language or write a song or design a home or build a computer game, maybe you ought to chase any of these dreams simply as a way to allow yourself to play and to play as well as you can only because honing a craft brings you pleasure. Not necessarily because there is any result at all attached to the outcome.

Here’s the cartoonist, Bill Watterson, described the years after he graduated from college. “I designed car ads and grocery ads in the windowless basement of a convenience store and I hated every single minute of the four and a half million minutes I worked there. When it seemed I would be writing about “Midnite Madness Sale-abrations” for the rest of my life, a friend used to console me that cream always rises to the top. I used to think, so do people who throw themselves into the sea. For the five years that Watterson drew grocery ads, he also drew comic strips on the side. Including one about a boy who had an annoying little brother who carried around a stuffed tiger. No one read what he was making. To endure five years of rejection he said requires either a faith in oneself that borders on delusion or a love of the work. I loved the work.

Words mean more than one thing to more than one person. Click To TweetEventually, a syndicate showed interest in the strip about the boy with the stuffed tiger. Within a year, Calvin and Hobbes are showing up 250 daily newspapers and not long after that, it was appearing about 2,500 dailies around the world. As my comic strip became popular, Watterson said, “The pressure to capitalize on the popularity increased to the point where I was spending almost as much time screaming at executives as drawing.” Cartoon merchandising as a $12 billion a year industry and the syndicate understandably wanted a piece of that pie. The more I thought about what they wanted to do with my creation, the more inconsistent it seemed with the reasons I draw cartoons.

The so-called opportunity I faced would have meant giving up my individual voice. It would have meant my purpose in writing was to sell things, not say things. Art would turn into commerce. In short, money was supposed to supply all the meaning I’d need. Watterson refused as I’m sure many of you remember. No Calvin and Hobbes t-shirts, no stuffed animals, no soft drink cups, no movie, no TV show and no theme park. He did his best to remove money values from the equation and drew the strip not to sell products but simply to draw the strip. Is that a failure or a success?

Here’s Virginia Woolf, “I desire always to stretch the night and fill it fuller and fuller with dreams.” Here’s Brian Doyle, a friend of mine who passed away, an exuberant novelist from Oregon. “If we do not dream that I think perhaps we are misusing our heads. They are not on our shoulders only to be farms for hair.” This is ultimately nothing more important than the dreaming that you fought through your failures of nerve. That you tried to execute your vision as carefully as you could, that you danced just to dance. Drew just to draw, sang just to sing, that you doubled your consciousness, suspended your disbelief, mirrored yourself, pursued your curiosity and built your suit of paper armor.

Once is Never: You can never control all the possible outcomes of any sentence you say or write. The best you can do is make the things as carefully as you can and then let it go.

Once Is Never

The night after the Halloween costume contest in 1979, I lay awake in bed for a long time and finally decided two things. One, that my mother did not know what she was talking about and two, that original was a synonym for crappy. For years, I thought this anytime the word original was employed in anything I ran from it. To be original was to be lousy, to be original was to be avoided, to be original was to fail. I wanted nothing more than to be the anonymous kid who sat down at the lunch table with a bologna sandwich, a bag of Fritos and a nice conformist carton of chocolate milk. As a working writer who sits at the keyboard every morning, I have to remind myself every day that it’s okay to accept failure. That language is only an arbitrary system of semblances and symbols. That languages live alongside living people billowing around us in this ever-changing, naturally selecting cloud.

Words mean more than one thing to more than one person and they mean one thing one day and another thing the next. In practice, as Bertrand Russell once said, “Language is always more or less vague, so that what we assert is never quite precise,” and he was right. Can the word tree ever do any more than approximate the great shivering, growing, clattering thing that is a tree? Can the word marriage ever come remotely close to suggesting the four defined confusing, exhilarating journey that is a marriage? The space between words and sentences in paragraphs lurks, snags, silences and pits into which we all as people inevitably must fall. You can never control all the possible outcomes of any sentence you say or write. The best you can do is make the thing as carefully as you can and then let it go.

As the Polish poet, Wisława Szymborska, said, “Poets, if they’re genuine must also keep repeating, ‘I don’t know.’” Each poem marks an effort to answer this statement but as soon as the final period hits the page, the poet begins to hesitate, starts to realize that this particular answer was pure makeshift. That’s absolutely inadequate to boot. The poets keep on trying and sooner or later the consecutive results of their self-dissatisfaction are clipped together with a giant paperclip by literary historians and called their oeuvre. The title of this talk comes from a German proverb Einmal ist Keinmal, Once is Never. Sometimes people take this to be an expression of futility as in what happens once might as well never have happened. As in if you try something and it doesn’t work, you should have never bothered to begin with, but others think it means something else.

They say maybe once is never means once doesn’t count so much. Maybe it means once isn’t forever or once won’t do any harm. Maybe it means it’s okay to make mistakes. That all are onces add up to something even if all onces are nevers. As Winston Churchill may or may not have said depending on what website you look up, “Success is stumbling from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm.” What a close to the paragraph from a novel I love, Steven Millhauser’s 1996 novel, Martin Dressler. In the novel, our protagonist Martin Dressler, he’s designed and constructed a series of hotels. Each one’s more popular, outlandish and commercially successful than the last but at the end of the book, Martin’s built this big final hotel. It’s a strange and massive vertical labyrinth called the Grand Cosmo. People haven’t flocked to it the way they have to his other hotels. The building is empty, and Martin is trying to understand how he feels about this.

The beauty is not the result but in the attempt to build our castles in the clouds, to sew a quilt, start a painting, or even write a single paragraph. Click To TweetFor a building was a dream, a dream made stone, the dream lurking in the stone so that the stone wasn’t stone only, but dream, more dream than stone. Dream stone and dream steel forever and lasting. Friendly powers that led him along dark paths of dream. They had been good to him. To hear Martin Dressler son of Otto Dressler, seller of cigars and tobacco, for really he had travelled a long way since the days when he ruled out old Tecumseh into the warm shade for he had done as he had liked. He had gone his own way and built his castle in the air. If in the end, he had dreamed the wrong dream, the dream that others didn’t wish to enter, then that was the way of dreams. It was only to be expected. He had no desire to have dreamt otherwise. Is this not Millhauser ruminating on commercial and critical success? Isn’t he questioning the ways we measure results? Isn’t he saying, “I wrote my books. I dreamed my dreams. If you don’t want to enter my books at least I dreamed them as well as I could and I have no desire to have done otherwise.”

If all of art-making as Thomas Bernhard suggested earlier is a catastrophe if our only tools are to use our clumsy ever-evolving system of symbols to fumble after a vision that dwells in a universe beyond symbols. If we can never fully realize what is often called the staggering promise of the unwritten, then why not measure success simply by asking ourselves if we dreamed our dreams with as much care as we could. No matter how few people bought it at the airport or clicked like on it, retweeted it or even brought it into the realm of their attention at all.

At a time when anxiety and depression are now the most common mental health diagnoses among college students, when some young people feel so much pressure to avoid making mistakes in front of their peers or their parents. That universities are reporting suicide clusters, when social media puts unrealistic pressures on Millennials to show perfect versions of themselves to peers. When a recent study at Duke described how its female students experienced enormous pressure to “be effortlessly perfect, smart, accomplished, fit, beautiful, and popular all without visible effort.”

When the director of the Counseling and Psychological Services at the University of Pennsylvania, a university which has seen fourteen student suicides since 2013 is quoted in The New York Times as saying, “For some students, a mistake has incredible meaning. We clearly need to be exploring different understandings of what it means for ourselves and our kids to fail and succeed.” In every human endeavor, a strange and unpredictable breach will always exist between what we can imagine and what we can’t execute. Between what we want to make and what we’re able to make. The important thing I’ve come to believe is to embrace that breach.

As I try to immerse myself in a new novel, I fail at the sentence level every three minutes. I try to get inside the character, make a sentence sound more musical and fill it with brighter images. I try to write a scene about a character getting nervous and the first thing that comes to mind is sweat prickles the top of her scalp. I erased the sentence. I try again and I fail again. It’s taken me 37 years to appreciate the wisdom of my mother that the beauty is not the result but in the attempt. To build our castles in the clouds, to sew a quilt, start a painting, compose a song, bake a pie, raise a family, engineer a better automobile or even write a single paragraph, we need to live with the fear that we will stink. That no one will pay attention that we will blunder about like fools. The fear that we will take our glorious, flawless, embryonic ideas and butcher them on the altar of reality. I hope that as you learn and laughed, you all head home a little more willing to pile up a big mess of black poster board and walk around with it in the rain.

Important Links:

- Tony Doerr

- Feel Free

- WebMD.com

- War and Peace

- Dubliners

- Lolita

- A Wrinkle in Time

- Gone with the Wind

- Harry Potter

- Sanctuary

- Remembrance of Things Past

- Martin Dressler

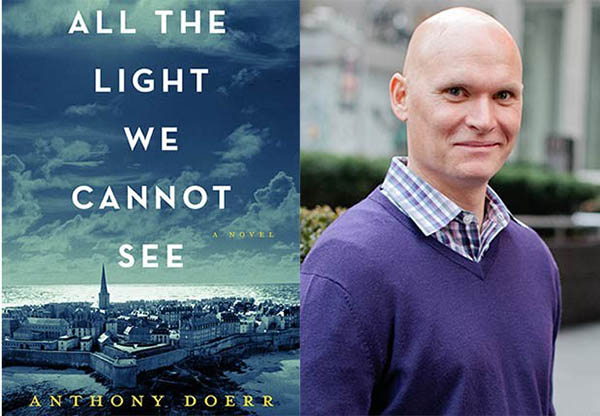

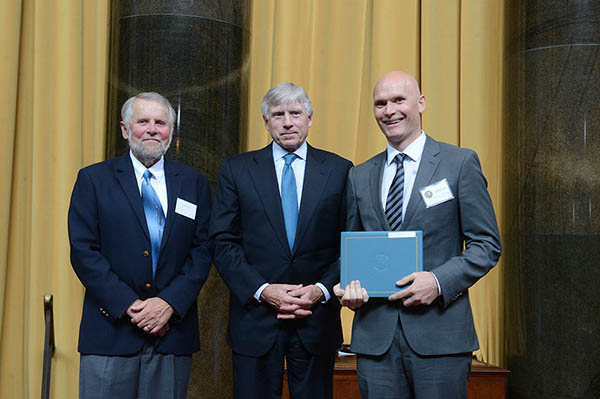

About Anthony Doerr

Anthony Doerr was born and raised in Cleveland, Ohio. He is the author of the story collections The Shell Collector and Memory Wall, the memoir Four Seasons in Rome, and the novels About Grace and All the Light We Cannot See, which was awarded the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for fiction and the 2015 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction. Doerr’s short stories and essays have won four O. Henry Prizes and been anthologized in The Best American Short Stories, New American Stories, The Best American Essays, The Scribner Anthology of Contemporary Fiction, and lots of other places.

Anthony Doerr was born and raised in Cleveland, Ohio. He is the author of the story collections The Shell Collector and Memory Wall, the memoir Four Seasons in Rome, and the novels About Grace and All the Light We Cannot See, which was awarded the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for fiction and the 2015 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction. Doerr’s short stories and essays have won four O. Henry Prizes and been anthologized in The Best American Short Stories, New American Stories, The Best American Essays, The Scribner Anthology of Contemporary Fiction, and lots of other places.

Anthony Doerr, Failure, Once is Never, Pulitzer, Success, Writers

His work has been translated into over forty languages and won the Barnes & Noble Discover Prize, the Rome Prize, the New York Public Library’s Young Lions Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, an NEA Fellowship, an Alex Award from the American Library Association, the National Magazine Award for Fiction, four Pushcart Prizes, two Pacific Northwest Book Awards, four Ohioana Book Awards, the 2010 Story Prize, which is considered the most prestigious prize in the U.S. for a collection of short stories, and the Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award, which is the largest prize in the world for a single short story.

All the Light We Cannot See was a #1 New York Times bestseller, and remained on the hardcover fiction bestseller list for 134 consecutive weeks. Doerr lives in Boise, Idaho with his wife and two sons. A number of media interviews with him are collected here. Though he is often asked, as far as he knows he is not related to the late writer Harriet Doerr. If you’re interested in reading some of his work online, you can find a number of essays here, a story at Granta, and you can watch the actor Damian Lewis reading part of Doerr’s story “The Deep” here.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Join The Coca-Cola CMO Leadership Summit Podcast community today: