Strength Through Stillness with Pico Iyer

So much information is flooding in on us every second that it’s getting harder and harder to tell information from misinformation, hearsay from fact, fake news from true. The result of that is that the world is coming to us as a never ending series of shocks. Nobody predicted last year that Britain or England was going to vote to leave the European Union. None one imagined that Bob Dylan was going to be awarded the Nobel Prize. This February at the Academy Awards, the most important prize of the evening was misannounced for the first time ever in history. It was almost as if it was an announcement that we are living in the age of inattention. We often hear these words thrown, “I’m really sorry, but things are crazy around here.” If that’s the case, essayist and novelist Pico Iyer says things are not going to get uncrazy. The only thing that can bring sanity to that situation is you. Discover strength through stillness as Pico talks about stepping out of your life just briefly to get the bigger picture and be reminded of exactly what matters to you most.

—

Listen to the podcast here:

Strength Through Stillness with Pico Iyer

This is the full presentation of Pico Iyer‘s talk title “Strength Through Stillness” from the 2017 Coca-Cola CMO Summit.

—

For me, it’s a special thrill to be here at an event organized by Coke. Kathy didn’t know this when she invited me, but I am a teetotaler. Ever since at the age of three, my drink of choice has been coke. As soon as I arrived in Atlanta, my first trip in 1995, my first morning, I went and made a pilgrimage to the world of Coke Museum. I’ve often pinned little hymns to that six-ounce bottle. I grew up in English boarding schools straight out of Charles Dickens and Harry Potter. We were only allowed to sleep in rooms named after extinct animals, pterodactyl, Tyrannosaurus rex. We had to wake up every morning before dawn and run through lines of freezing cold showers. We were served grill for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Some of you may have seen Oliver Twist in which the little boys ask for more and get in trouble. We were always asking for less. That didn’t help at all either. There was one highlight in our school year and there was a kind of lottery and if you were the winner, for one Sunday you would get an exemption from the school lunch. Instead you will be handed a little paper bag with a small bag of potato chips, apple, a bar of chocolate, and the crowning glory, a six-ounce bottle of Coke. On the very rare occasions when we won this, we would take a bounty up to our rooms. We’d go and get the compass from our geometry sets. We would put tiny little holes in the bottle cap and then probably giving ourselves lead poisoning, we would suck this elixir for the next 480 minutes, extending it through the day and exalting and not having to go to lunch. I never dreamed as I was drinking that heavenly nectar, that one day I would be in Silicon Valley at an event organized by Coke.

I’m feeling a little embarrassed because we’ve got to see these dazzling multimedia presentations throughout the day. You look at the front of the room and you just see this shifty character reminiscing about his boarding school days and no clicker insight. One reason is that I’m so on top of the digital economy that I can barely turn on a laptop without setting fire to the house. I apologize because I know it can be really difficult just to listen to one person in one corner of the room babbling away.

I was at Google a few years ago and I was just talking to them as I’m talking now. Fairly early on I looked across the audience, everyone was looking just suicidal. They were looking desperate. I realized it was because they were waiting for the show to begin, for me to stop talking and start projecting slides. Finally, I heard myself say, “I’m really sorry, but I don’t even have a PowerPoint.” It’s guaranteed everything I say is going to be powerless and pointless.

What can I offer to a room full of CMOs? I thought the one thing I can be guaranteed of is that you are overwhelmed. My sense is that almost everybody now is dizzy and getting dizzier with every passing season. You in particular because your job involves finding cool, digital, new ways of passing the news about new products and so many people are depending on you. You are probably overburdened. My sense of the world now is that so much information is flooding in on us every second. It’s getting harder and harder to tell information from misinformation, hearsay from fact, fake news from true. The result of that is that the world is coming to us as a never ending series of shocks.

Strength Through Stillness: Almost everybody now is dizzy and getting dizzier with every passing season.

Nobody I knew predicted last year that Britain or England was going to vote to leave the European Union. None of my writer friends imagine that Bob Dylan was going to be awarded the Nobel Prize. No so-called pundit or expert in this country predicted correctly the result of our last election. At the Academy Awards, they made the wrong announcement of the most important prize of the evening for the first time ever in history.

The Age Of Inattention

It was an announcement that we are living in the age of inattention. I notice in my own life because I’ve been working with the same company and sometimes the same colleagues for more than 30 years now. My most well-organized colleagues who are absolutely on top of things, lose everything I send them nowadays. They never get back to my messages. When occasionally I do hear from them five months later, it’s to say, “I’m really sorry, but things are crazy around here.” My sense is that if that’s the case, things are not going to get uncrazy. The only thing that can bring sanity to that situation is you. In some ways, I thought the most useful thing I could offer you, because this has been a very rich and stimulating day and you’re probably waiting for the reception, is the chance to take a break.

If some of you find yourself nodding off, almost think of that as a compliment or approve that I’ve have succeeded. During the last hour as we were singing, I was remembering this winter day, many years ago when I got into my car and I drove up into the cold, high dark mountains behind Los Angeles. Near the top, where there was almost snow on the ground and the signs prohibited the throwing of snowballs, I pulled into a rough parking lot. There was an old stooped man in a ragged gown, with wire rimmed glasses and a woolen cap who was waiting for me. As soon as I got out of my car, he gave me a deep ceremonial bow, though we’d never met before. He insisted on carrying my things into the little cabin in which I was to sleep.

As soon as we got to the cabin, he started slicing up bread and then putting on water for tea, cooking dinner. He even asked me if I needed a wife though I was well taken care of on that front. He was so anxious to don his attention on me and so invisible that for the longest time I didn’t realize that this man in tattered monk’s robes was my hero since boyhood, the great singer and poet, Leonard Cohen. Leonard Cohen had already been famous for 40 years at that point, famous mostly as this very cool man of the world. He was famous for his beautiful suits and his beautiful girlfriends. Maybe because of that, he had decided to come to this remote mountain top sanctuary and live for five and a half years as an ordained Zen monk. Scrubbing floors, shoveling snow, and especially looking after every need of the then 88-year-old Japanese head of the Mount Baldy Zen Center.

I visited in the dead of winter, the monks were going through a retreat that involved more or less seven days and seven nights of uninterrupted meditation. Occasionally they would take a break, they’d walk around the mountain, but that was a form of meditation too. Nearly all the monks were in their twenties, in their early thirties. Leonard was 61, but he was putting himself through this discipline with unwavering determination. Very late that night, he came down to my little cabin and as he was picking dirt out of his shoe, he said that being there, just sitting, still looking after his friends, being unplugged, was the real deep entertainment he had found in life. The profound, voluptuous, and delicious excitement that the world had to offer. I was crushed, because he’d been my hero. He was my hero because of his romantic lifestyle, his beautiful girlfriends, and his constant wanderings. There was no doubting the kindness, the attention, and the modesty that he brought to every moment.

I’ve been working for Time Magazine for more than 35 years. I’ve met my share of eminences, but I realized I had never met somebody as poised, as articulate and as unimpressed with himself as he. As I got in my car and I drove back down the mountain, I thought, “Well, here’s this man who has tasted all the pleasures the world has to offer. Everything that sex, and drugs, and rock and roll can serve up, and he’s found his great joy and great adventure just sitting still.”

Sitting Still

You all know that sitting still has always been a part of the human experience for as long as there have been humans, but I don’t think it’s ever been such an urgent necessity as right now. In the time you’re reading this, our human race is going to gather twelve times more data than exists in the entire library of Congress. It’s quite a thought. Every one of you, even if you weren’t at this summit, would be taking in more information today alone than Shakespeare did in his entire lifetime. Does that mean you’re wiser than Shakespeare, that you know more than he did? I’m not so sure. I think it might almost be the opposite.

Your kids are going to spend eleven years of their lives on the phone. In Sacramento, researchers found a young woman in high school was handling 300,000 text messages every month and that’s an impressive figure. It means that if she sleeps for eight hours a night and I very much hope she does, she is still handling ten texts every waking minute of our life. If she takes a shower for twenty minutes, she has to handle 220 texts the next minute to sustain that average. The remarkable thing is they found this woman ten years ago, before smartphones are common. She would probably be up to 3 million texts by now. She wasn’t a CMO, she wasn’t a mother with four little kids, she was just a regular high school student.

There’s this great new field with the wonderful 21st century name of interruption science. Researchers have found that it takes the average person 25 minutes fully to recover her concentration after a phone call. In a room such as this, the average person receives a phone call every eleven minutes. I’m sure you know the sensation that the more you try to keep up with the moment, the further you fall behind. I suddenly find myself in this strange predicament whereby I do have more and more time saving devices in my life, but it feels like I have less and less time. I have more and more data at my fingertips, but less and less chance to make any sense of it. I can more and more easily make contact with people on the furthest corners of the planet, from Tibet to Timbuktu, but in that very process, I seem to lose contact with myself. We heard that people are working fewer hours than they were 100 years ago, but researchers have found that we feel as if we’re working more. Clearly, something is going wrong.

Nomophobia

The bottom line is simple. Human beings were never designed to live at a pace determined by machines. The only way we could do that is by becoming machines ourselves, which even in Silicon Valley, I don’t think very many people want. We were meant for living at the speed of light but as we heard, we’re obliged now to live at the speed of light. I’m sure all of you in your families and in your workplaces, perhaps in yourselves, have seen the new neurological effects of all of this. Doctors report more and more cases of nomophobia. The medical condition of being terrified of being outside mobile phone contact. There are said to be 280 million people on the planet already addicted to their smartphones which means that if they formed a community, it would be the fourth largest nation on earth. Our devices are more addictive than the most addictive drugs because with our devices, unlike with heroin, we have to use them to some extent.

Strength Through Stillness: In some ways, our devices are more addictive than the most addictive drugs because with our devices, we have to use them to some extent.

We can’t really function without them, but once we use them a little bit, it’s very difficult not to use them more. I think you probably know that the World Health Organization has said that the health epidemic of the 21st century is not Zika, it’s not Ebola, it’s not SARS, it’s stress. According to statistics, 50% of the physicians in this country are said to be suffering from burnouts and of course they’re the ones that the rest of us depend on for our well-being and our health.

Everybody in this room would put their money on one sure thing, our devices are not going to go away, and our devices are not going to get slower or less potent. We wouldn’t want them to. The technology unequivocally has made our lives longer, healthier, brighter, and more interesting. Without technology I wouldn’t be able to see you without my contact lenses and without technology I wouldn’t be able to hear you without my hearing aids. As somebody with asthma, without technology I probably couldn’t breathe. If you are feeling dizzy at all now, you will be 100 times dizzier ten years from now because all of this is exponential.

All of you know that as long as you’re looking at a screen, you can’t see the larger picture. It’s only in the margins of our lives that we have room to explore, to try new things, to get lost. The main text is much too crowded. All the driverless cars and all the 3D printers in the world are not going to help us if what we’re copying and what we’re transporting is no better than before. There’s one great place of light and hope in this landscape and that is the problem is never in our machines. They’re just neutral instruments that obey our commands. The only problem is in ourselves and our failure to make discerning use of our machines. If the problem is in ourselves, so too is the solution.

The people who are wisest about placing limits on technology are the very people who gave us these technologies. Share on XI’ve been traveling for years, almost incessantly, everywhere from North Korea to Easter Island. One of the biggest surprises of my travels is to find that the people who are wisest about placing limits on technology are the very people who gave us these technologies. All the brilliant engineers are around us in the Valley. You will see people doing a really good job of getting their jobs done tomorrow by playing beach volleyball in the sand outside their offices. You will go to every other building on the Mountain View campus and see a meditation room and probably a trampoline in everyone. I remember many years ago, I was at Google and a couple of my friends were telling me that there were 1,000 Yoglers who are not just Googlers who practice yoga, but Googlers who have been trained to teach yoga.

I was up at the TED Conference in Vancouver and I was suddenly asked to do an event with the Co-founder of Twitter, Evan Williams. I have never met him before but I bumped into him in the corridor on the way to our lunch. He was wearing a button that said, “Talk to me about reading, writing, and obvious ideas.”This was not what I had expected. In my ignorance I hadn’t known that the man who helped to create 140-character communication form is most committed now to long-form journalism. When we had our lunch, I found Mr. Williams to be uncommonly quiet, reflective and deep. He kept on saying that he just couldn’t imagine how anybody could navigate the modern world without a meditation practice. He led his entire staff every morning in meditation. When the man who has brought into our language not just the word tweet but also the word blogger says something, I’m inclined to listen.

Internet Sabbaths

Some of you may not know that Kevin Kelly wrote his great book about the technological revolution without a laptop, without a cell phone, and without a television in his home. Here in Silicon Valley, many people observe Internet Sabbaths. They go completely offline for 24 hours at a time or 48 hours, or 72 hours every single week so that they’ll have something creative and fresh to offer when they go online again. They know that machines have given us everything except a sense of how to make wise use of our machines. We have a curious double standard when it comes to this.

I remember a few years ago I went for my annual checkup with my physician and he looked at my blood test results. He said, “You seem okay, but you’re not getting any younger, so you should do 30 minutes of intense cardiovascular activity every day.”I signed up at a local health club and I religiously do my exercise every day of the year. A few weeks later I was back in Kyoto, Japan where I live. I was talking to a very wise friend and he said to me, “All you spend your time doing is answering emails, flying around, living in airports. Have you never thought of just sitting quietly for 30 minutes without your laptop in one corner of the room every morning?” I said, “No way. I don’t have time.” I realized what silly and short sighted answer that was.

It was as if I’d said I don’t have time to take my medicine. I don’t have time to visit the doctor. I don’t have time to be happy because in some ways that’s really what it’s about. I sometimes tell myself, “If I’m happy racing from text message, to conference call, to CNN Breaking News update, to Facebook status update, I should certainly continue.”Something in me suggests that that’s not where my joy, or my fulfillment, or my inspiration come from. If ever you hear yourself say, “I’m too busy to help my kids with their homework. I’m too busy to meet my friend for coffee. I’m too busy to answer my friend’s email”, you’ll know something is out of kilter and you’re the only person who can put it back in proportion.

In every country in the world, through every century, people have agreed that those who are wise are never too busy. Those who are busy are never to wise or too happy or too kind. I am most happy when I forget the time and when I lose myself. If I’m wrapped up in a movie, or in rich conversation with a friend, or an intimate moment with somebody I love. I’m least happy when I’m all over the place, and scattered and fragmented. Many of us have this great gift for running away from our happiness and then wondering why we’re so lost and confused.

I had a very typical Californian experience. I was in my parents’ house, the family home, just four hours down that freeway, the 101 in the hills of Santa Barbara. I saw this distant line of orange cutting through a hillside, so I went downstairs to call the fire department. When I came upstairs, five minutes later our house was encircled by 70 foot flames that were being whipped on by a 70-mile per hour winds. One of those fires regularly tearing through the hills of California and many other places. This happened to be the worst fire at that point in Californian history. I was caught in the middle of the fire for three hours. When finally I was able to escape, every last thing my parents and I earned in the world, every photo, every souvenir, every note, every keepsake was ash.

Those who are wise are never too busy and those who are busy are never too wise or too happy or too kind. Share on XI had to go down to an all-night supermarket and I bought a toothbrush. I went to sleep on a friend’s floor. I was sleeping on that floor for many months to come. Another friend who was a school teacher came in and he saw me on the floor and he said, look, “I’ve got a better alternative.” He told me how every spring, he took his classes up to a retreat house in Big Sur, California. According to him, even the most phone addicted testosterone adult and fidgety fifteen-year-old Californian boy only had to spend three days in silence. Something in him calmed down and cleared out to the point where he didn’t actually want to return to his regular life. I thought, “Anything that works for a fifteen-year-old boy sounds perfect for me.” I asked my friend, “What exactly is this place?” He looked a little embarrassed. He hemmed and hawed and then he said, “It’s a Catholic hermitage.” Wrong answer. I’m not a Catholic and I’m not completely a hermit. I looked at the floor and I thought, “Anything must be better than this.”

Pulsing Silence

I got in my car and I drove three hours north along the coast. The California Highway 1 north of San Luis Obispo gets narrower and emptier until you’re just in this vast elemental landscape with golden fields on one side of you and the great still shining blue Pacific on the other. I came to an even narrower road that’s barely paved that snaked for two miles up to the top of a mountain where the monastery sat. When I got out of my car at the top, the silence was pulsing. It wasn’t just the absence of noise; it was the presence of probably everything I walk or sleep walk past the rest of the time. I went down to the little room in which I was to sleep, which was small but very comfortable. There was a single bed and a long desk and an even longer picture window looking out on a small walled private garden. There’s 1,200 feet of golden pampas grass running down to the ocean, which stretched in every direction.

A couple of minutes later, a blue jay alighted on the fence in my garden. I just watched it, transfixed. Blue jays would constantly alight in all around the house where my parents lived, which was exactly the same altitude. I’d never thought or stopped to look at them. A few minutes later bells began chiming in the chapel behind me, and I felt as if they were charming inside of me. After night fell, I went out of my room and under this great orbital salt shaker of stars, I could see the taillights of cars disappearing around the headlands twelve miles to the south. I’ve never felt happier or calmer or clearer. It was seeing my life from the top of a mountain, putting it in proportion and remembering what I care about. I am being reminded of exactly what matters to me most and therefore what I should do for the next six months. It was striking because only seven hours earlier when I was driving up there, as usual, I was fretting about deadlines, worried about obligations, conducting arguments with myself or with some phantom friend. All of that completely fell away. I began returning to that place. I’ve been there more than 80 times.

Strength Through Stillness: It was like seeing my life from the top of a mountain, putting it in proportion and remembering what I care about.

When I’m lucky I’ve been there for a week or two, but sometimes I just go for a day or two. If the retreat rooms are full, I even stay with the monks in the cloister. I realized in time that the place itself is not important. There are places like this in your hometown, whichever hometown that happens to be. There are places like this in your backyard. There are places if you are sufficiently settled in yourself, you could find this kind of peace in Times Square on a Saturday night. The place is not important.

The only thing that’s important is choosing to step out of your life, just briefly. It really takes courage to tell your bosses, “I’m not going to answer emails for the next 72 hours.” It takes courage to walk away from your kids. It takes courage to miss a friend’s birthday party. My feeling is it’s only by doing that you’ll have anything joyful, fresh, and invigorating to offer to your kids, your bosses and your friends. Otherwise you’re just foisting on them your exhaustion, your distractedness, which is no blessing at all.

All of you are in the business of telling stories. The simpler and clearer the story, the more effective it is. You can only get that simplicity and clarity by stepping out of your life and stepping out of the world to see the world from the trees. Some of you have had that experience of going into a museum and you’ll find yourself maybe one foot away from this big crowded, constantly shifting canvas. You realize as you stand there, you have to step back and then further back. When you are twenty-feet away, does it click into focus and can you see what the canvas is saying to you? Can you catch the larger picture? That’s exactly how it is with our lives and with the world. When you’re in the thick of it, you can’t make them out.

I suspect during this vicious circle whereby we’re in such a hurry, we can’t see what a hurry we’re in. Unless you stop to collect yourself, you may find there’s no self left to collect. I’m embarrassed to be saying this because I know that every single one of you is already doing probably many things every day to open up space in your schedule and in your beings. Some of you do practice meditation. Some of you practice yoga. Some go for a run every day, play golf, play a musical instrument, cook, or go sailing. As the world accelerates, you could probably gain from doing more.

Meeting Myself

The great financier, JP Morgan, was famously saying he was giving himself two full months off every year. He said he could never achieve in twelve months what he achieved in ten. I have a friend at Google who at the beginning of the week makes appointments with himself, so he’ll look at his calendar and he’ll say from 3:00 PM to 4:00 PM on Tuesday, I’m going to meet myself. Which means maybe he closes his eyes, maybe he goes for a walk, maybe he just collects his thoughts, but only by meeting himself will he have anything to bring to his other meetings. We need all this, for the sake of our sanity. We also need it because whoever you are and however successful you are in your job, life is going to make a house call, more than once.

I remember I was asleep in my room in Japan. Suddenly the phone began to ring in the dead of night. Good news never seems to come at the dead of night, but I fumbled my way through the darkened apartment. I picked up the receiver and I heard this strange voice saying, “Pico Iyer.” I said, “Yes, that’s me.” He said, “No, I need to speak to Pico Iyer please.” I said, “Speaking.”He said, “You don’t know me, but my name is Spencer. I am a nurse here in Cottage Hospital in Santa Barbara. Your mother has just had a stroke and two days from now she’s going to go through a six-hour surgery. You’re her only living relative. It would be a good idea if you were back here.”

The simpler and clearer the story, the more effective it is. Share on XI scrambled to gather all my things. I was on the next flight back and I ended up spending the next 35 days in the ICU with my mother and she’s fine now, but it was really a touch and go for a long time. As I was sitting there, I was thinking about all the emails I’ve answered, all the emails I’ve sent, all the trips I’ve taken, none of that is really going to sustain my mother or support me in this moment. The only thing that could help is whatever I’ve gathered inwardly in my inner savings account.

3% Rule

Even before that, I had made for myself a 3% rule. I’d worked out that if I go on retreat for three days every season, that’s only 3%of my days, but it completely transforms the other 97%. If I were to follow my friend’s suggestion and sit quietly for 30 minutes every morning in my room, not doing anything, that’s only 3% of my waking time. It would clarify and eliminate the other 97%.

I’ve tried to incorporate lots of just tiny everyday things into my routine to give myself a break. When I’m on the treadmill, I love watching NFL football, but I’ll turn the TV off. Suddenly my mind can just run like a dog off the leash or crash out if that’s what it needs. When I’m driving around town, I love listening to the radio. Sometimes I’ll turn the radio off. I’ve got a mini vacation. As a writer I found that all my best work takes place when I’m away from my desk, when I’m playing tennis, or watching a movie, or talking to friends. In your work that for much of the time you have to be at your desk because you need the data, you need the details, you have to be there to micro-organize everything and put it into a pattern.

To think outside the box, to radically reconfigure a situation, to come at something from an absolutely fresh angle, for that, you have to be away from your data and be able to clear your head in many ways. Every evening in our apartment in Japan, I’m waiting for my wife to come back from work and I never know if it’s going to be twenty minutes or 70 minutes. I used to just kill the time as it were. I’d scroll around online, I check my emails, I turn on Japanese TV. I thought, “Why don’t I just restore the time?” I turned off all the lights and I put on some music. It’s very quiet music at first, Bach or Sigur Rόs, but then not so quiet music. Green Day works, The Who, The Clash, you name it.

When I turn off some of my senses, I was amazed at how much fresher I felt when I heard my wife’s key in the door, how much better I slept, how much less jangled I was when I woke up the next morning. I think the last twenty minutes of the day and the first twenty minutes are disproportionally important for your sanity because that’s how you’re planting the seeds for your unconscious. It will work when you’re asleep. The first twenty minutes because that’s how you set the tone for the day to come. I try very hard to go as long in everyday without going online as possible. It’s not always long, but at least I have that aspiration. I never go online for maybe an hour, ideally two hours before I go to sleep. When I’m on a plane, I pretend there isn’t any Wi-Fi. It has become one of the great sanctuaries in my life. I keep a notebook there and I let my mind for six hours if I’m flying across country, go every possible place.

Strength Through Stillness: To think outside the box and to come at something from an absolutely fresh angle, you have to be away from your data and be able to clear your head in many ways.

Before we end, let’s return to our man on the mountain, Leonard Cohen. Some of you may know that after his five and a half years as a monk, he was getting close to 70, he thought he should spend more time with his kids. He went back to the very simple modest house in a really beat up part of Los Angeles that he shares with his daughter. Soon after returning to the world, he found in his absence, while he’d been meditating in the monastery, somebody had made off with just about all the money he’d saved over 50 years, as much as $20 million. He had just about nothing to leave to his son, his daughter, and his grandchildren. At the grand old age of 73, he had to go on tour again. For the next six years, he gave 380 concerts everywhere from Hanging Rock, Australia to Istanbul, from San Jose down the street to Nova Scotia.

I went to see him three times at the beginning of this tour. In his mid-70s he ran onto the stage every night. He sang for more than three hours every night. Much of the time he kneeled before his fellow musicians as if they were the main attraction and he was just a bit player. Most of all, I think from having seen him in the monastery, I could tell he was bringing all the passion, the intimacy, the intensity of the meditation hall right into these great musical arenas. Many people said that it was the finest concert they had ever seen. As the tour went on, the strangest thing began to happen. His old song, Hallelujah, became the fastest downloaded single in the history of Europe. At the age of 77, he released a new album with a very unsexy title, Old Ideas. It went to the top of the charts in seventeen nations across the planet.

If you want to be moved, you have to sit still. Share on XSuddenly this warm, weathered, old man, long past retirement age, had really become the prince of fashion and one of the most cherished and sought after musicians on the planet. Much more important, whenever I went to see him in his very humble house, I met the wisest, calmest, and seemingly most content person that’s ever been my privilege to meet. Leonard Cohen died, but his songs, his poems, his video recordings are giving people sustenance and will continue to do so for decades to come.

The last time I checked, one of his YouTube videos alone had 75 million views. What he had realized by sitting still was that it’s really essential to make a living can’t do without that. It’s no less essential to make a life. If you really want to be moved, you have to sit still. It’s very hard to be moved when you’re running around. In this age of almost post-human acceleration, the greatest luxury can be going slow. In this amazing age of distraction, nothing feels more sumptuous than attention. If you only want to do justice to your children, to your colleagues, and to yourself, please give yourself a break and give inner peace a chance.

Important Links:

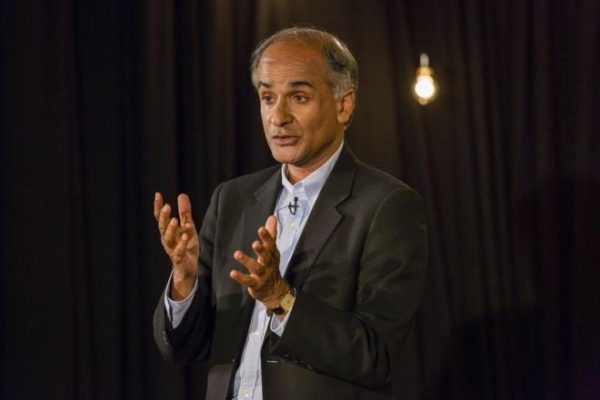

About Pico Iyer

Pico Iyer was born in Oxford, England in 1957, to parents from India, and educated at Eton, Oxford and Harvard. Since 1986 he has been writing books and since 1992 he has been based in rural Japan with his longtime sweetheart, while spending part of each year in a Benedictine hermitage in California.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Join The Coca-Cola CMO Leadership Summit Podcast community today:

3% rule, age of inattention, nomophobia, Pico Iyer, sitting still, strength through stillness