The Exploration of Uncertainty with Pico Iyer

Even before uncertainty became a buzzword, we have had to deal with it every day, but the situation we are facing now forces us to take a harder look at it and accept its reality. This conversation between Kathy Twells and Pico Iyer, a writer and travel enthusiast, is an exploration of uncertainty – an inquiry on how we can navigate the unfamiliar landscape of the world during COVID-19. As a traveler, Pico knows that more often than not, the best and worst things happen to you when you’re not exactly on the beaten path. Sometimes, you just have to let life run its course and not beat yourself up for things you cannot control. This theme of surrendering to life pervades much of this discussion, but it’s not as simplistic as it sounds. You’ll have to listen to know more. This episode is a powerful one and something that we all need to hear as we face this uncertainty together.

Even before uncertainty became a buzzword, we have had to deal with it every day, but the situation we are facing now forces us to take a harder look at it and accept its reality. This conversation between Kathy Twells and Pico Iyer, a writer and travel enthusiast, is an exploration of uncertainty – an inquiry on how we can navigate the unfamiliar landscape of the world during COVID-19. As a traveler, Pico knows that more often than not, the best and worst things happen to you when you’re not exactly on the beaten path. Sometimes, you just have to let life run its course and not beat yourself up for things you cannot control. This theme of surrendering to life pervades much of this discussion, but it’s not as simplistic as it sounds. You’ll have to listen to know more. This episode is a powerful one and something that we all need to hear as we face this uncertainty together.

—

Listen to the podcast here:

The Exploration of Uncertainty with Pico Iyer

Navigating The Landscape Of Our Unfamiliar Territory

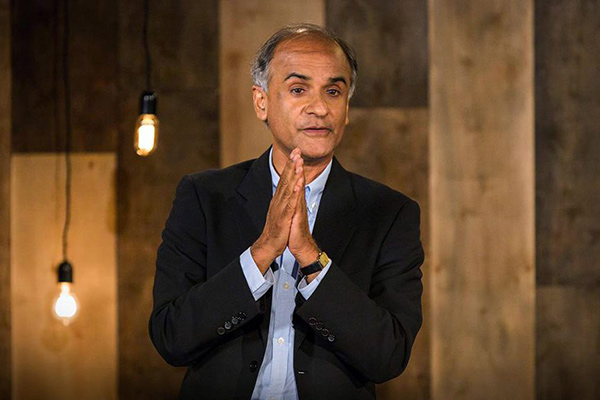

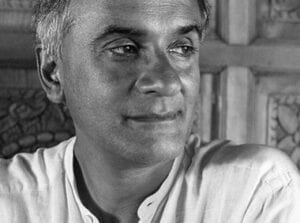

I am pleased and honored to share my conversation with my friend and mentor, Pico Iyer. He joined us at the CMO Summit in 2017. He continues to be an incredible voice of wisdom to all of us as we manage the changes in the world around us. Since 1982, he’s been a full–time writer publishing fifteen books translated into 23 languages on subjects ranging from the Dalai Lama to globalism from the Cuban Revolution to Islamic mysticism. They include such long-running sellers as Video Night In Kathmandu, The Lady and the Monk, The Global Soul, The Open Road and The Art of Stillness. He’s also written the introduction to more than 70 other books. At the same time, he has been writing up to 100 articles a year for Time, The New York Times, The New York Review of Books, The Financial Times and more than 250 other periodicals worldwide. His four talks for TED have received more than ten million views so far. This is an incredible human doing such beautiful and soulful work in the world. I am honored to know him and to share the conversation on the show with Pico Iyer. Please enjoy.

—

Pico, welcome to the show. I have to tell you I am grateful that you are spending this time with us. Thank you for doing this. I’m delighted to have the chance to talk to you again, Kathy. Thank you for inviting me.

The Power Of Stillness

I’m sure you remember we met in 2018 when the CMO Summit was going on in Silicon Valley. It was an exquisite summit. We were talking all about distraction, technology and all the craziness. You had this beautiful talk about stillness. It was the perfect antidote to all the technology conversation. I’m grateful for that. What I want to do before we get into talking about all the wisdom, I know you’ll share with us is to have you ground everyone in your origin story. I do an intro on the show, but I love to hear from you a little bit about you to our readers. How did you cultivate your life journey up to now? I was born in Oxford, England to parents from India. When I was seven, my parents moved to Santa Barbara here in California. From the time I was in the second grade, I almost had three sets of eyes. I also had an English voice, American green card and Indian features. I remember even then I was thinking, “This is rather lucky. I’ve been given three ways of looking at the world, three different perspectives. I can mix them together. I can play them off one another. I can look at England through Indian eyes. I can look through California through English eyes. This is a rare blessing I’ve been given.” I never thought then that soon this would be the norm. When I was a kid, this was unusual. Because of the very different educational systems and the exchange rates then, I started to go to school by plane from the age of nine. Every couple of months I’d get on a plane and fly alone over the North Pole to my school in England. Every couple of months fly back to see my parents. That set into motion in my life balanced between travel and stillness. When I finished my education, I was lucky enough to get a job at Time Magazine in my twenties. I had this exciting high paced life in Midtown Manhattan. When I was about 29, I thought I’m having such a good time, I could easily wake up and find I’m 70. I’m about to die and I’ve never lived. I’ve never explored any other options. I thought since I had no dependents and I could live simply when I was 29, the perfect counterpoint to my life in the 25th floor office four blocks from Times Square is to go to the back streets of Kyoto, Japan to a single room, no telephone, no private toilet, no anything. Whatever happens in Japan is going to be different from what I experienced in New York. I can’t take anything for granted. Just going to the supermarket is going to be an adventure. I did that. Many years later, I still live in Japan in a tiny two–room apartment with my wife. I suppose my life has become this balance of breathing in and breathing out. I still travel a lot everywhere from North Korea to Antarctica to Easter Island. I come back home and sit still for a long time at my desk as writers do and try to make sense of what I’ve experienced and to extract the meaning from this bombardment of sensory details, emotions and encounters. I almost think that travel for me is like experience for all of us. It’s like going to the Farmer’s Market and gathering lots of spicy ingredients. It’s only when I’m sitting still at home that I can take all those ingredients and turn them into a meal. I‘ve been very lucky to have these two components in my life and to feel that they play off each other. Your story is exquisite and unique, the whole three lenses. How many people who have this amazing job in their twenties in Manhattan, which for many would be considered the high life and so full of stimulation and suddenly, you want to make a change. That speaks volumes about the unique view on the world that you have and has informed who you are now. I love it when you talk about breathing in and breathing out in this processing time. I do find and I see this in myself, we tend to go all the time and maybe we miss things when we don’t stop and have that stillness and that processing time. Can you share a little bit more about what that’s done for you as a writer and as a human over time by doing that? A leader is somebody who, at some level, knows that they’re no better than anybody else. Share on X First, it’s hard to be moved unless you’re sitting still. If I’m driving on the 405 Freeway in LA racing from appointment to appointment, I don’t have a chance to open my heart or to be transformed. It’s also, as you were saying, hard to make sense of the world when you’re racing from place to place. It’s only by stepping back from the world that you can put it into proportion. For me, it’s very much as if more and more in this accelerated age, we’re standing about 3 inches away from our lives. There’s no way we can even see what’s important there, let alone find out the deeper meaning or possibilities. I always feel that the challenge with a cluttered schedule is the same as with a cluttered desk or with a cluttered mind, which is when something important happens, you can’t put your hands on what’s essential. The trivial and the indispensable all mixed up and suddenly a car is driving the wrong way down the road towards me. I can’t grab what most I need or a fire starts surging above the hills and the other ones have. I can’t put my hands on what I most need to take with me. As our world accelerates, it’s harder and harder for any of us to remain in control. I was talking about Time Magazine and I remember when I was working there, there were about 100 of us. It was a weekly magazine. We worked very hard until midnight on Thursdays until 4:00 in the morning on Fridays. We put together 40 articles a week that were fairly rigorously fact–checked, proofread and strong. I met a friend from Time Magazine. I said, “How’s the weekly magazine?” He said, “Forget about the weekly magazine. We have to post 100 articles a day online.” We have a smaller staff than we did when I was in the Time & Life Building. People are having to do seventeen times as much work in Time Magazine, but at Coke and at every company I know, we can’t keep up with that. That’s not a human way to live. The first thing we lose in that process is our humanity. The second thing we lose is our sense of proportion. My heart went out to my colleague when he said that. I thought how hard it was for us even to be doing 40 articles a week.

Leadership In Uncertainty

I don’t remember the stat, but there’s some science about how many pieces of information are coming into us at any given time. It’s some astronomical amount. Everything we’re sensing, reading, seeing and feeling, but our brain can only process so much of it, a very small percentage of it. We’re constantly filtering all this out. When you step back and think about it, it’s a crazy time that we’re living in. We’re in the middle of this global pandemic. The world is shifting all around us on many levels. We’re going to talk more about that as we go through the conversation. I want to touch on leadership. The readers, we’ve got people from all countries. We have people who are leading in business. We have people who are leading their own personal lives, from all ages and every walk of life. The origin of the summit has been about leadership and about community. For my own leadership and those that I know, we’re trying to figure out how to navigate this world. One of the things at Coca–Cola is we talk about being in a growth mindset. The growth mindset means you fail and you learn. It’s not about perfection. It’s about figuring it out as we go with the best knowledge that we have. Here we are in this very strange world. How would you think about leaders modeling when the answers are way more elusive now than they’ve ever been? There’s a lot more vulnerability. How would you share some lessons on that? The virus is clearly a dictator, but it’s also an equal opportunity. In a curious way, as you were suggesting, we’re all in this together. None of us knows more than anybody else. In that sense, it’s very democratizing, as you said, whichever country you’re in, whichever religion you happen to follow, whoever you are, you’re in an equal state of bewilderment. I was reading a book in which it said very interestingly how every town in Italy has a tower, but the only place that most of us seek out is Pisa because the tower is crooked. It’s leaning. It’s not perfect. I remember I used to cover the Olympic Games for Time magazine and the hugest bursts of applause that would come in, every race would be when somebody fell and hobbled towards the finish line. That was the person, the whole audience was with much more than the Usain Bolt or any of the guys who were running quickly because that person is us. We all know how that person feels. A leader is somebody who at some level knows she’s no better than anybody else and who rejoices in that fact that she’s walking side by side, even though in certain ways she has to take decisions for the other people. As you probably know, I’ve been lucky enough to spend 46 years talking and traveling with the Dalai Lama. One of the great things I’ve learned from him is that when people ask him questions, one of his most frequent answers is, “I don’t know.” Often when I traveled by his side across Japan every year, and I attend all his public events, nearly always somebody will ask him a question about raising children or about marriage or something like that. He’ll give his wonderful irrepressible love and say, “I don’t have a clue. You’ve asked exactly the wrong person. I’m a celibate monk. You know much more than I do about marriage. I don’t have the first piece of experience.” One of the most moving things, when I listened to Pope Francis speak, is he ends every talk by saying, “Please pray for me,” and that always shocks me. He’s the Pope, but he’s saying he will gain from our prayers. He’s not the guy on high, just blessing all of us. In some ways, the virus moment is a time when all of us are in the desert. We don’t know what’s going to come around the next corner. We’re reminded of what we’re all asking questions. They’re probably the same questions. It’s questions that open doors much more than answers, which tend to close them.

Exploration Of Uncertainty: Questions open doors much more than answers, which tend to close them.

You used the word vulnerability because at this moment more than ever a leader is obliged to share her vulnerability with the people around them. That’s what’s going to bring her closer. At some level, all of us are looking for guidance, which is why we turned to Pope Francis and the Dalai Lama because we want them to shed light on all of this. In this instance, they don’t have the answers any more than we do. I did a public conversation with the Dalai Lama. He doesn’t know what the answer to the virus is, but he does know that all of us have the capacity to try to make not a fight against reality, but work with reality and to say for better or worse, this is the hand we’re dealt right now. What positive things can we bring out a bit? Many business leaders, certainly spiritual teachers talk about this. The more we swim upstream or fight against what is it does not lead us to the Promised Land. There’s an element of surrender. I love how you talk about being in the inquiry because we need to ask different questions. The questions are very powerful. They can create so many new answers and new insight if we go into new questions. As I was listening to your origin story and what a remarkable young person you were to pick up and leave New York, travel and change things. As I think about you as a writer and all the places that you’ve been, you’ve traveled all around the world and whatever I’ve gone to, a new culture and different place, it’s always about getting out of your comfort zone and going to unfamiliar territory. That’s going to grow you because it’s new and different. Here we are finding ourselves in our homes in unfamiliar territory. How would you speak on that knowing it’s such an odd time to be living in?

The Art Of Getting Lost

As I was listening to you, I was thinking that the art of travel is the art of getting lost. It’s only when you’re lost that you’ll find what you never thought to look for. In other words, I remember the first time I took my wife to Paris. I knew she would want to see the Eiffel Tower and the Louvre. I also knew that the memory that she would take back from that trip would be some back street cafe that we stumbled upon, not listed on any guidebook, not known to any of our friends, but we could feel that’s something that we’ve discovered about ourselves. It’s only because we didn’t know what we were doing or where we were going in some ways. You and I have been talking about how to some degree our lives have been out of balance and out of control these last several years, maybe, and this virus has almost given us a chance to put things into balance again. As I say that I’m aware that your colleagues and many of the people in this conversation are probably working harder and assuming twelve hours a day and more exhausted in the normal run of things. Nonetheless, being confined to one space as most of us have been, we’ve been reminded of a whole different set of values because when we’re at work, we have one set of priorities having to do with productivity and efficiency. When we’re at home, we have another set of values having to do with humanity, kindness and fulfillment. Those who of us were working at home, we’ll see those priorities colliding, but we also have the chance to bring some of those more humane priorities to our working life. To think that when we go back to our offices, what can we have gained from this moment that will make us better able to engage with colleagues and clients when we’re caught up in our normal routine? I was talking to some sales representatives and they were saying how difficult it is to try to pitch something over Zoom and how they have to make an extra effort to be personal, to make human contact and to use their emotional intelligence. I thought none of that’s going to be wasted once they’re back on the road again and having dinners with their clients. All of the emotional subtlety that they’ve had to master can only help them and the people around them. I remember once I was here in my family home in Santa Barbara and I did see one of those balls of flame approaching over the mountains and my house was burned to the ground. I lost every last thing I had in the world. After I’d adjusted to it, I started noticing that in certain ways it was opening doors and windows that I hadn’t been aware of. When the insurance company came along and said, “We’ll replace all your possessions,” I didn’t need 90% of the books, clothes and furniture I’d accumulated. I could live much more simply. All my notes were handwritten so I lost all my next three books. My next eight years of writing, but I thought I’m still preoccupied with certain subjects. I’m going to have to try fiction. I’m sure I would have been too shy or scared ever to attempt it before. I thought to myself, “My physical home here in Santa Barbara doesn’t exist anymore. Maybe I can spend more time in the home of my heart, which is Japan, the place I felt like my deepest home.” In all kinds of ways, maybe a year after the fire, I was living much closer to the life I’d always imagined. This thing that was such a shock at the time in many ways set me on to the course that now I’m enjoying. When you first asked me about my origin story, I probably should have said my second birth and my most important birth came with that forest fire that liberated me to be closer to the person I should have been all along. Four hundred and fifty other households were destroyed in that fire and my neighbors were traumatized to this day by it. Now, it’s such a common occurrence across California and the world. Quite a few people after a year would say, “My life is no worse off than before the fire and in some ways, I have a better way of seeing what to do.” It’s such a powerful story, Pico. I’m not going to get the credit on this because I don’t recall who said it, but there was a quote of, “The barn is burnt down. Now, I can see the moon.” I’m sure you’re familiar with that. It speaks to what you’re saying. Things appear in our lives that at face value seem difficult or bad and they may be indeed difficult or tragic in some cases. If you see all of your belongings, your work and your art are suddenly gone. What we don’t often see are the gifts on the other side of that, things we didn’t know we needed, an insight that was coming to us that we didn’t have. Often, we make judgments immediately about our preferences for our path. We soon realized that we’re not in control of how those things come about. I wrote to my editor, the person who edits all my books at the publishing house, I said, “For my next book please, you tell me what to do because what comes to me out of the blue will be better than what I think of in relation to preferences. It’s because I’m moving along the same old roads that I know too well. When somebody else, whether it’s Kathy or my editor in New York suddenly says, “Write about such and such,” I’m jolted out of it. I’m much better able to come up with something fresh. I’m happy you mentioned the barn poem. It’s uncanny that you do because I should tell you I was caught in the middle of that far for three hours. I was on our mountain road watching the fire systematically go through our living room, the bedroom and then my office. When I finally was able to drive down, I went to a friend’s house where I used to sleep on the floor for many months. The first thing I had to do is call my poor mother, who was away in Florida and say, “At the age of 60, you’ve lost, after escaping the fire was to find a computer because my job was still to be a columnist for Time magazine to send them an essay. For once in my life, this breaking news event, at that time, the worst fire in California in history and our house was one of the first it hits. I was able to deliver a story then and there. Be still. Give yourself a break. You’ll be doing yourself and everybody else a favor. Share on X I ended that story the night of the fire with the poem about the barn. Even then I intuited the house burned down, I can now see better the rising moon, as you said. Even the night of the fire, something in me realized this isn’t only a bad thing. During this virus, all of us are thinking first of the people who’ve lost their lives, their loved ones, their livelihoods, people without a roof over their heads. None of that can be wished away, but for those of us who were lucky enough to emerge from this with our bodies and living to some extent intact, certainly there’s the potential here. Because we’re being forced to live in different ways and there’s no way of seeing that the way I’m living right now is entirely worse than the way I was living in August of 2019. We’re keenly aware of all the things that were missing from our regular lives, but our regular lives went so easy. For example, this is my typical way of living. In one week, I flew from Terra del Fuego to Buenos Aires to Houston to Los Angeles to Santa Barbara to San Francisco to Osaka. Three continents in a week is pretty much how I’ve been living all my life. I got something wonderful out of it. I’m sure I caught a cold. I’ve contracted jet lag. I remember I was standing outside my house at 4:00 in the morning, waiting for the taxi to take me to the airport. The taxi never showed up. Now I can romanticize the life I had then, but when I was living it then, it was full of its own challenges too. I remember in 2018, the whole conversation at the CMO Summit in Silicon Valley was about the onslaught of information, distraction, all the technology and keeping up with the advancements. Our CMOs were trying to figure out, “How do I stay ahead of it?” The anxiety level was tremendously high. Perhaps it wasn’t quite the same collective anxiety and unknown that we have now but there’s no question. You see many people talking about this in social media and among friend groups that it’s not like the old way was necessarily Nirvana. We were having other challenges. You and I exchanged emails and had some conversation about like, “What does stillness look like now?” I follow you on Twitter and you always tweet such wonderful nuggets that are thought-provoking. They always enhance my day. One of my most favorite books that you wrote and one that you shared with us at the Summit was The Art of Stillness. You tweeted something that said, “Monks, as professional explorers of the inner landscape, know one essential thing: there’s nothing more dangerous than sitting around and nothing more clarifying than sitting still.” You talked about this ability to process in between breathing in and breathing out. You’re not traveling as you said, none of us are moving like that. We might be still, but sitting around and still is not the same. Can you share a little bit about the distinction between those two things? The bigger distinction is maybe between the stillness that we choose and the stillness that’s enforced. I remember when I wrote the book on stillness, I said that people who are incarcerated, people who are invalid, people who are still in and they want to be, nobody wants to be in that position. I have traditionally been in a luxurious position to go and choose to be on a retreat or to set up my desk. That’s the way I wanted it to be. As you say, all of us have to make a living, but the living we make will only be as good as the life we’ve made around it. How to make life has to do in a savings account, resources or you said, the only way we can understand the world and make sense of it and make the most of it. One example is twenty hours after California went into lockdown in March, my mother who’s 89 was rushed into a hospital in an ambulance. She was losing blood. I was in Japan then. I gathered all my things and I was on the way to the airport when I was told I couldn’t go to the hospital anyway because it was close to visitors because of the lockdown. I was forced to stay in Japan. A few weeks later, she came out. I took three flights in the middle of the lockdown from Japan back to California. When I arrived at my mother’s house and I was sitting next to her, I thought, “What can I bring to her right now?” She’s fragile. She’s 89. I thought, “My checkbook is no help at all. My resume is not going to be of any use to her. All those places I traveled in January are not going to sustain her or support me.” The only thing I could bring her at that moment is what I’ve gained in sitting still. My movements aren’t going to produce anything that would help her. The time I spent sitting still, which might bring me some clarity or some calm or one hopes some kindness, that’s the only real resource I have to bring to the situation. All of us have many situations like that all the time, whether it’s an earthquake or family illness or Coronavirus. Stillness is in some ways the most important investment we have for life that’s always going to be out of control and unpredictable. We’re lucky that so much of the time it feels like is in control. What you were saying at the beginning of your question makes so much sense. Earlier too, I read that people are working less nowadays in the United States than in the 1960s, but we feel as if we’re working more. Some things were overwhelmed. Something is going wrong in the process. The other statistic that I’ve heard, which you were mentioning was that every one of us takes in more data every day than Shakespeare did in his entire lifetime. Does that mean we’re wiser than Shakespeare? I think not. In fact, it might mean the opposite. We’re taking too much data we can’t see the wood from the trees. That’s partly what stillness means too, which is freedom from clutter again. If I have three things on my mind or on my desk, I can get much more out of them than if I have 3,000. Stillness is partly about sifting. That’s why I know you have a meditation practice, do yoga and take walks. Probably everybody reading this conversation does something take runs or plays golf or go sailing. Our world is accelerating more and more and it’s not going to get slower. The data is intensifying and it’s not going to diminish. Our devices are getting stronger and stronger. They’re not going to get lesser. Each one of us has to make very conscious investments to ensure that we’re not drowned under all the stuff that’s coming in on us and he took two whole months off every year. He said, “He could never achieve in twelve months what he achieved in ten months.” In other words, taking a break makes you more productive. What I found during this virus moment is I’ve taken many more walks than I would normally. I’ve taken more breaks. I’ve tried to stop working every day at 3:00. I also try to, for example, never to go online for two hours before I sleep, which means that I tend to sleep better and I wake up much less jangled than if I check my emails before I go to sleep. Simple things like that, making appointments with oneself. It’s only by making an appointment with oneself, which means you take a break, you take a walk, you gather your thoughts, that you have anything to bring to your other appointments. Otherwise, they’re coming in one after another. Many of the people in this conversation know the sensation these last few months Zooming twelve hours a day. You can’t bring anything to the Zoom conversation number eight if you’ve been moving from one to the other. You’re doing everybody a favor if you stop and take a walk around the block or do whatever it is that helps you get oriented. The more the world is spinning around, the more essential stillness is. Right now, there’s a different spinning that where we’re not physically moving, but so much has come in on us. I think again, we have to give ourselves a break to keep our sanity intact.

Exploration Of Uncertainty: Stillness is, in some ways, the most potent investment we have in life.

It’s very interesting, Pico, because I would say if I were to listen to probably the last 5, 6, 7 podcast conversations that I’ve had, there is a very definitive theme. There’s this theme about what the exact thing you’re talking about, this idea of spaciousness and about the idea of how do we find our optimal way of being? It does require this balance and it comes up again and again. We know this. There’s this wisdom, but yet we struggle to do it. I’ve been in conversations with people who will say to me, “I struggle being still. My mind is so busy. The demands are busy. I think about school is about to begin again and mostly online.” We have mothers and fathers trying to balance work and having their children at home, trying to learn. There is a sense of overwhelm and trying to figure out how to support that. You mentioned the blending, you see people’s lives or it’s all blending into one thing. When that happens, it requires discipline with yourself to give yourself the gift of spaciousness. It’s a practice where we’re all having to learn. It’s tough. I should stress when I talk about stillness, I don’t mean so much the necessity of physical stillness as giving yourself a break. When I wrote that book about the art of stillness, I took great pains. I never use the word ‘mindfulness.’ I never used the word ‘meditation’ and I’d never had a meditation practice. I know some people are scared of it. It’s intimidating. It’s formidable. For those people, I would say again, “Take a walk around the block or turn off the lights and listen to music or you work in the garden.” It takes myriad forms. It doesn’t have to be sitting there. Those even sitting in your room without your devices for twenty minutes, it’s not actual meditation, but you’ll come out of those twenty minutes healthier. I mentioned it to the Summit. As soon as my doctor told me I needed to go to a health club and do 30 minutes of cardiovascular activity, I signed up and I do that 30 minutes religiously every day except during this virus season. If somebody were to say to me, “Pico, why don’t you spend 30 minutes being quiet every day?” I’d say, “I don’t have time. I don’t have the luxury.” That emotional or mental health club is much more important to our wellbeing than a physical one. It’s not going to do me any good if I’m toned and muscular and my mind is falling apart. Make that time going to the health club. We can make that time for sanity, kindness and bringing something clear to ourselves, our jobs and our families. For example, one thing I started doing many years ago was to try every season to go for three days to a Catholic Hermitage in Big Sur. I know you’ve been there too. I’m not a Catholic and I’m not completely a hermit, but it’s an example of that investment whereby going there for three days transforms my next few months. Every time I go there, I’m frazzled and distracted. I’m feeling guilty about going there and leaving my elderly mother behind, not being available to my colleagues for 72 hours. As soon as I come back down Highway 1, 72 hours later, I’m full of energy, joy and clarity and I know what I should do for the next three months. I have that overview and I’ve given my system an oil change the way I do in my car. The way I recharge my devices, I’d recharge it with my entire being. Sometimes three days, every season is only 3% of all the days of my life, but it makes such a difference. We get ourselves into thinking, “I don’t have time to take time out for myself.” If you don’t, you are going to be moving backwards and doing damage probably to your work and to everyone around you.

Navigating Uncertainty

We do share a love for this place that you speak of. I also find it’s so beautiful there that when you’re surrounded by beauty and the closer you get to nature. It’s tremendously healing and powerful. I’m setting the tone for us moving forward. I want to move to a connected conversation, but a little bit around time and the essence of past, future and present and how we’re managing that. Returning to leadership again, here you are. For all of us trying to figure out, how as leaders do we paint a vision of the future? Part of leadership is I want to show you a compelling place that I want to take you and rally everyone to follow into this beautiful new world we’re creating. None of us have ever had crystal balls, but now more than ever, there’s that uncertainty for leadership about how do I paint this vision of a future? What would you say to leaders who are standing here as people are looking to them? You mentioned the Dalai Lama and others saying, “I don’t know,” and we’ve touched on this already, but it’s even tougher now. How would you speak to leaders about the future? It’s tough, but I know as a writer and a traveler, I’m the worst offender when it comes to all these things. When I’m working on a book or an article, I take great pains to make an outline. When I’m taking a trip, I map out my itinerary every hour for the next two weeks, let’s say, but even as I’m doing that, I know that as soon as I arrive in Paris, things are going to take an unexpected turn and I’m going to have to throw my itinerary out the window. I’m glad to make the plan as it were because that gives me a sense of confidence and guides me towards where I need to go. It reminds me of what the final destination is. In every case, I know and I almost hope that things will go different from my plan and a writer knows. I think it’s the same in every job that I map out the project, but I’m hoping that they’ll get so deeply into it, that it takes on a life of its own. It’s making me more than the other way round and things I didn’t even know I have inside me will come out of me. Suddenly, I end up in a destination I couldn’t have imagined. That’s how it must be with your colleagues and with everybody. None of us ever have crystal balls. For me, the virus has underlined, which is always the case, which is last year and five years from now. I can never tell you what’s going to happen the next day or the next night. We’re always speculating. If it’s not a virus, it’s something good or bad that comes out of nowhere. It could be a forest fire. It could be a windfall. Nonetheless, we’re always in the dark and we shouldn’t pretend otherwise. Because we’re in the dark, we need to hold a flashlight. Especially as you say, as a leader, one needs to say, “Come on, everybody. Let’s go there,” but you know that things are unlikely to go exactly the way you hope. As I’ve been saying, I’ve lived in Japan for a long time. One of the first things I learned there was that wherever you go in Japan, as you’re walking down the street in Kyoto, the bells are tolling about impermanence. Nothing lasts forever. This is about to change. The signs all say the same thing. Life always makes better decisions than we do. Sometimes the best thing to do is to let it run its course. Share on X Even the kids in the neighborhood, when they’re learning the alphabet, have a little chant like our Pledge of Allegiance. It’s supposedly about flowers, change, clouds and move on. Even we, kids are not going to be here forever. It took me a while after I arrived in Japan to realize that the fact of impermanence or uncertainty, isn’t a recipe for grief. It’s a recipe for finding what we want right now in an uncertain world. The certainty is at this moment. I’m talking to Kathy and this is a great delight. I haven’t seen you for a couple of years. We’re both relatively healthy on a beautiful mid-summer Californian afternoon. I can make the most of this. Since I don’t know what will happen tomorrow or next year, let’s find my inspiration, my wonder, my beauty right now. The Japanese talk about life as joyful participation in a world of sorrows because at some level, every meeting ends in the separation, every birth ends in death. We lose many things, whoever we are. That’s not a reason to despair. It’s a reason to embrace and fully to make use of what we do have, which is right now, and nothing will take me away from the fact I get to talk to you about important things. It is a true joy and delight that we are able to do this. It is all at this moment. There would probably be people who would debate me on this. If we did have a crystal ball, it wouldn’t be so good because not knowing is a part of the mystery. If you knew, people say, “I want to know.” I don’t know. That would be a little boring if we knew because like that cafe you discovered that wasn’t on your itinerary, it is off the beaten path. It’s the things that happen to us that truly transform our experience in life, which is amazing. In business, we have to do scenario planning. We have to look at what might happen because we have stakeholders and we have teams and people. We certainly do our best, but there cannot be rigidity in that. We have to continue to not react to what happens as much as respond with that space. Having a little bit of space to respond and know that we’re going to figure it out. We’re going to find our way, even in the uncertainty that we are all facing. That’s one of the many strange blessings that this moment will bring us. When your company and every company is gathering for its planning meetings next year, we all remember this thing could happen again. I often feel I’m very blessed because throughout my lifetime, I’ve never known a world war and I’ve never learned something that’s overturned my life dramatically on a global level. Most of us, we’re reminded these things happen and we can’t pretend they’re not going to happen. I’ve been thinking of reality as one’s partner or one’s sweetheart, who is often difficult and sometimes impossible, but we have to make a life with her or him. We can make a wonderful life with her or him, partly we’re difficult and impossible too. I love the way you express yourself. You certainly know you’re a writer because of all the beautiful ways that you paint these pictures of what we’re talking about. If you don’t mind getting personal with what you’ve had to endure. You’re a travel writer, you speak all over the world and all of a sudden people aren’t gathering and people aren’t traveling. You’ve spoken to some of this, but how have you managed adapting to this? I‘ll have to confess, Kathy, that as soon as the world stopped moving in March, it’s very quickly, I had 23 consecutive speaking engagements canceled. The whole revenue for the year flew out the window. A part of me thought coming into the window instead of calm, sanity and creativity. As a writer, I can’t remember the last time I had five consecutive months at my desk to write. I’ve inflicted on my poor editor, three manuscripts since the lockdown began, all I’m sure unpublishable. For a writer, it’s a curious thing to have to spend a lot of one’s time traveling to speak. I know I first got to meet you of course, through a speaking engagement, but it’s reminded me in my own life that maybe I had things I’m a little out of proportion before. I’ve been thinking to myself because I was rejoicing with many of these cancellations. Maybe something is telling me that I could do with a little less movement in my life and a little more time at my desk. After all, I chose to be a writer at an early age, and now I’m going around talking. Maybe something is telling me to stay put and be a writer more. When I first left New York City at the age of 29, I was saying to myself, what I most want are freedom and time. Income and security are not so important, but I want every day to last a thousand hours. That was a wise decision I made early in my life and often I forget it. I get caught up in these habits and these routines that aren’t necessarily the ones I would select if I was given a blank page. Now, I have been given a blank page. As I say, I have to make a living and support my loved ones. I’m sure I will be doing speaking engagements again next year I hope, but maybe I don’t have to be doing many of them. Maybe I can re–orient my life to give me a chance to think about what would be the balance that I would choose in an ideal world and now the world will never be ideal. At least, I’m consciously thinking about it rather than falling into this routine. Otherwise, I might not have. All of us have experienced a couple of other things during the virus. My wife and I have lived in this little apartment in Japan for many years. We’ve never taken walks in the neighborhoods. We started doing that twice a day. Lo and behold, four minutes from our little apartment, we came upon this amazing bamboo forest with flowering cherry trees, nightingales teaching their young to sing. Four minutes, three blocks from our apartment, we’ve never been there in many years. I’m now at my mother’s house in Santa Barbara, which my parents have been on this property for many years. For the first time in many years, I’ve taken walks up the mountain road. Now, I do it with my wife every morning. Suddenly my eyes are opened to what I otherwise take for granted, which is I’m here in Southern California, above the ocean on these glorious springtime and midsummer days. This is the scene that people would give their lives to be able to enjoy. I’ve been sleepwalking past them. Now, every day suddenly I’m enjoying them. I hope going forward once I am flying around the world more as I used to, I will still take these walks when I’m back in Santa Barbara. As with this conversation, you and I met a couple of years ago, but we haven’t had a chance to talk to right now in person. I’ve been receiving emails from friends and from strangers and they’re thoughtful, long searching emails. I’ve been thinking when I was emailing my old friends in January, we’d be talking about Meghan and Prince Harry or what are Tom Brady’s prospects now that he’s been knocked out in the first round of the playoffs, essential stuff but not so much essential. Now when my old friends write to me or strangers from all over the world write to me, they’re writing about uncertainty, solitude, doubt and hope, all the things you and I have been talking about and what a blessing, what a gift. My friends and I that I’ve known since I was in high school would probably never address that or would tell ourselves we don’t have time or space to address that normally.

Exploration Of Uncertainty: If we focus on what we have, it brings us gratitude. If we focus on what we don’t have, it gives us frustration.

Now, each of us has been moved by circumstance and new conditions to do so and another great blessing that’s come into my life. At any given moment, we can concentrate on what we have or concentrate on what we don’t have. If we concentrate on what we have, it usually brings us a certain degree of gratitude. I think to myself, “I’m lucky my mother is still alive at 89. I’m doubly lucky. She’s got this beautiful house in California. I and my wife are healthy and everybody we know so far.” If we concentrate on what we don’t have, it leads to frustration. You were saying this, I have a friend who is a palliative physician. He’s working with the dying. He says, “Suffering comes from wishing things to be other than the way they are.” If somebody is in their last moments and they accept that, they can do a lot in those final moments. If they’re always fighting against it, it’s always going to be a rather tragic situation. This moment I think has reminded all of us of that basic truth. I definitely see a pattern in our conversation, not at all to belittle the challenges and the suffering and the losses that have occurred this year. Whether it’s losing your home to a fire or having any unexpected, what certainly at face value is a difficulty or tragedy happen that within that, there are always gifts to be found. As I asked my team the question, what are you learning? How will you be different as you think about your travel schedule? How will you balance that differently and create the space to flow with it instead of feel compelled to do so many stops and so many engagements? Throughout the thread of this conversation, we’ve seen the power of surrendering to what happens and then allowing us to be evolved and taught from the things that are happening. Pico, I so value this conversation with you. I have one last question for you. This is completely open-ended and we’ve talked about a lot. As we close out, think about your whole life experience. All the things that you have shared, is there 1 or 2 things that the wisdom you’ve gained that you would share with the people reading now as we conclude our chat? I suppose that the world is always bigger than our ideas of it, which we’ve spoken about in some ways, and that life or fate or whatever you want to call it makes much better decisions than we would. In other words, I never saw this when I was young when I was very carefully plotting out my next many years or cutting out the whole of my life. At this point in life, I would say that everything that’s come to me good and bad has come out of the blue. It’s never been what I expected. Suddenly out of nowhere, I’ll get a dream job. Suddenly years later, my household burned down. Suddenly, I’ll step into a temple and meets up with the woman who becomes my wife. When I was in my twenties, I thought, as we were saying before about making a plan, I will set out my plan for life and go through it the way I did preparing for exams at high school. That hasn’t been how things have gone. I’m very grateful for that because so much has happened in my life I wouldn’t have had the sense to ask for. I suppose the one other thing I would say is and this speaks to everything we’ve been saying about the virus season. That it’s never easy at the time or for a long time to see whether an event is good or bad. When we’re in the thick of it, we assess it one way and many years later, we see it very differently. It’s interesting. There’s a wonderful book called Happiness by a French scientist who became a Tibetan Buddhist monk, Matthieu Ricard. Early on his sites when people win the lottery, when researchers go and talk to them a year later, they say, “We won $10 million last year, our lives are no better than they were before.” We spend all our time with the lawyers. We don’t know who our true friends are. We’ve moved into this new upscale neighborhood and we’re not comfortable. I’m not sure that they’re worse than before, but our lives are no better. When people speak to those who’ve been suddenly rendered paraplegic in an accident after a year of adjustment, they’ll say, “Our lives are no worse than they were before.” Some things are very difficult that we took for granted. We’ve had to change in so many ways, but people are kind to us. We found all the resources inside ourselves we didn’t know. I wouldn’t say that my life is better or worse than it was before. That seems to have been the thread through all our conversations. I suppose if I were to reduce it to two words, I would say that every event in life has brought me humility and wonder. Those are probably my life’s companions. Most of all, what you were touching on, surprise. I can’t by definition I don’t know what surprises are ahead of all of us and me individually. I’m sure they’re going to be interesting. I’m sure they’re going to be more imaginative. If I were to tell you, Kathy, this is what I’m going to do in the year 2021. Life is going to come up with something much more creative. Humility, wonder and we’ll add surprise to that. I will take those words with me from our conversation. I’m grateful again for your time. I know that everything you have shared has been a gift to everyone who has been reading. I value your friendship and I value everything that you give to the world. Thank you so much, Pico. Thank you, Kathy, for keeping up for your rich correspondence with me and for inviting me to be part of this conversation. Also, for bringing into your immediate community and corporate environment these kinds of imaginative, soulful ideas because all of us will be richer for them. Thank you for this show and thank you for this chat.

Important Links:

- Video Night In Kathmandu

- The Lady And The Monk

- The Global Soul

- The Open Road

- The Art of Stillness

- Pico Iyer

- Happiness

About Pico Iyer

Pico Iyer was born in Oxford, England in 1957. He won a King’s Scholarship to Eton and then a Demyship to Magdalen College, Oxford, where he was awarded a Congratulatory Double First with the highest marks of any English Literature student in the university. In 1980 he became a Teaching Fellow at Harvard, where he received a second Master’s degree, and in subsequent years he has received an honorary doctorate in Humane Letters. Since 1982 he has been a full-time writer, publishing 15 books, translated into 23 languages, on subjects ranging from the Dalai Lama to globalism, from the Cuban Revolution to Islamic mysticism. They include such long-running sellers as Video Night in Kathmandu, The Lady and the Monk, The Global Soul, The Open Road and The Art of Stillness. He has also written the introductions to more than 70 other books, as well as liner and program notes, a screenplay for Miramax and a libretto. At the same time he has been writing up to 100 articles a year for Time, The New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the Financial Times and more than 250 other periodicals worldwide. His four talks for TED have received more than 10 million views so far. Since 1992 Iyer has spent much of his time at a Benedictine hermitage in Big Sur, California, and most of the rest in suburban Japan.

Pico Iyer was born in Oxford, England in 1957. He won a King’s Scholarship to Eton and then a Demyship to Magdalen College, Oxford, where he was awarded a Congratulatory Double First with the highest marks of any English Literature student in the university. In 1980 he became a Teaching Fellow at Harvard, where he received a second Master’s degree, and in subsequent years he has received an honorary doctorate in Humane Letters. Since 1982 he has been a full-time writer, publishing 15 books, translated into 23 languages, on subjects ranging from the Dalai Lama to globalism, from the Cuban Revolution to Islamic mysticism. They include such long-running sellers as Video Night in Kathmandu, The Lady and the Monk, The Global Soul, The Open Road and The Art of Stillness. He has also written the introductions to more than 70 other books, as well as liner and program notes, a screenplay for Miramax and a libretto. At the same time he has been writing up to 100 articles a year for Time, The New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the Financial Times and more than 250 other periodicals worldwide. His four talks for TED have received more than 10 million views so far. Since 1992 Iyer has spent much of his time at a Benedictine hermitage in Big Sur, California, and most of the rest in suburban Japan.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Join The Coca-Cola CMO Leadership Summit Podcast community today:

COVID-19, Exploration Of Uncertainty, Getting Lost, Humility And Wonder, Leadership In Uncertainty, The Power Of Stillness