Cultivating Leadership Through Community with Kelly Leonard

Leadership has become a well-worn word, something that people talk about all the time. We tell ourselves that there is one person out there who’s the genius and who’s going to fix everything. Occasionally, we think it’s ourselves and we’re always wrong. The reality is we work in groups. There are always new insights to be had, but one of the things that we’re seeking to weave throughout is this whole idea of leadership through community and the importance of the connections to each other. Kelly Leonard, a CMO Summit alum, discusses about why our connections to each other matter and why this idea of community is so important that we need to really cultivate it.

Listen to the podcast here:

Cultivating Leadership Through Community with Kelly Leonard

We are coming to you from Second City in Chicago where we are kicking off the very first episode of the CMO Summit podcast. We’re launching this with the conversation with one of my favorite people, Kelly Leonard. Kelly is an alum of the CMO Summit. He joined us a couple of years ago and he’s continued to be a wonderful friend and resource over time. We’re going to talk about a lot of things and certainly the core topics that we speak about at the summit. Leadership, of course, being at the heart of the matter. The leadership has become a really a well-worn word, something that we talk about all the time. There are always new insights to be had but one of the things that we’re seeking to weave throughout this podcast is this whole idea of leadership through community and the importance of the connections to each other. Why that matters is we co-create something new moving forward. We’re going to start broad and then get a little bit more into Second City. Talk to us about why our connections to each other matter and why this idea of community is so important that we need to really cultivate it.

I think we’re fighting the great American myth which is the loan magic person who takes care of everything. It’s run rampant. It’s the story we tell ourselves. We tell ourselves that there is one person out there who’s the genius and who’s going to fix everything. Occasionally, we think it’s ourselves and we’re always wrong. The reality is we work in groups. We happen to be fairly dysfunctional at it often, but we need to think of ourselves. This is the way we do it at Second City where we think of ourselves as an ensemble. I have an example for you from a program. We just created a program called Improvisation for Caregivers. We developed this with Ai-jen Poo who is the co-director of Caring Across Generations. She was Meryl Streep’s date at the Golden Globes. You might have seen her there. I got introduced to her by Adam Grampp, the author, and we hit it off.

In our conversations about her work and our work, what kept coming up was that, especially in the care-giving community, the weight of the world is on these people’s shoulders. They feel like they are alone and many of these people are parents, they’re caring for their elderly parents or children or whomever, but they feel they’re doing it alone, and in fact, they’re not. Part of what we’re teaching in this program is an ensemble orientation. How do you change your mindset to recognize that there are lots of people involved here. I’ll shift it to a business context. How do you realize and make yourself own the fact that it’s not you alone, that you have lots of people to draw on? It’s not just the people you work with. It’s also who your audience is. You’re all part of this greater ensemble, this extended circle. When we can shift our orientation out of that ‘me first’ or ‘me alone’ mindset, a lot of stuff opens up to us.

This happens all the time certainly in the corporate realm, probably everywhere where there’s this sense of scarcity. It’s an old nature of competition where if I hoard information, I have information that you don’t have somehow, I’m going to get ahead. When the real truth of the matter is, the more we collaborate, the more we work together and help each other succeed. Everybody is able to be better for it.

There’s data behind this. There’s actual science that says that the more you help others, the more likely it is that you’re going to succeed. The more that you are others-focused, the more you’re going to see. This is the other thing: if we want to get to things like truth and if we want to get the things like success and if we want to get to things like happiness, all of this stuff is important and it’s important for our customers too, by the way, then we need to think of ourselves inside our various groups. By the way, these groups morph and change and they’re different. Some people call them tribes. There are different languages that different experts will give to you, but really it’s this whole idea, and we’ve talked about this before, which is I don’t understand why in business, people check their humanity at the door. It’s all we have.

It’s almost like there’s this sense of wearing a mask and this certainly happens with people where you feel like you need to put on some persona that is very safe and that only reveals so much of yourself; and that if there’s too much humanity, there’s too much of the real self coming in that really makes us feel vulnerable in a sense. At the last summit, our topic was all about how do we balance our humanity with this unbelievable growth in the digital evolution. We’re more connected now than we’ve ever been, yet for so many people, they’re actually more alone because they’re missing that real dynamic in person connection that we’re losing from all of the connectivity. Part of our conversation is this real balance between our real-life connections and our humanity and this incredible world of digital that we’re seeing.

The number one problem in humanity now is isolation.

I was talking to Dr. Samuel Wells, who is the vicar of St. Martin-In-The-Fields. This guy wrote a book years ago about improvisation and Christian ethics. His theory was that the number one problem for humanity used to be mortality and we’ve solved that pretty well. People are living to ripe old ages. He said what he believes the number one problem in humanity now is isolation. When you look at the digitally-enabled world and if you’re looking to fight the robot narrative, what you need to recognize is the one skill that is going to survive as things become more and more automated is all the things that make us human: problem solving, creativity, innovation, vulnerability, authenticity, and storytelling. This is why English majors have it right. Believe me, I’ve researched because I have an English major in college right now. The ability for him translate stories and to relate to other people. These are the skills that are going to be needed in the future of work, and increasingly, I find that there’s a tension between those two.

I think what’s interesting about that is the juxtaposition with what you just said and with what you led off with at the beginning of the conversation where you talked about there isn’t that singular person, that singular thing; but then, when you think about what technology has done, it has isolated us in a way that’s made all the things that you talk about so very important. I think that one of the things that I’d love to explore a little bit more with you is the idea of the power of the ensemble. In the sense that we see this in business all the time where it’s that singularity, that one person that feels like they have to own it and get everyone else involved.

Ensemble is not only important, it’s critical.

In the world that you live in, ensemble is not only important, it’s critical. It’s everything to success. I’d love for you to talk a little bit about the power of the ensemble and how that translates into success on the stage when vulnerability that your cast members put on themselves, not only going up in front of an audience, but also at times accepting suggestions from the audience, could be a very uncomfortable place yet the success rate I assume is very high. I’d love to hear thoughts about that.

The success rate becomes high after we fail a bunch. There’s a bunch of things to unpack here. The first thing is recognizing. We have a phrase that all of us are better than one of us. What we certainly know is that individuals carry with them all these biases and confirmation bias being the worst among them. That’s the one where you’ve got the one person in the room who’s the boss, and basically, everyone is seeking to agree with them. That does not lead to good decision-making and it doesn’t lead to good results. It’s also the thing that gets everyone in trouble, ethics wise.

I was just at a learning conference and they put the stats up of how many companies are left from 25 years ago in the Fortune 500 and it’s something like 17% and then these brands keep going up and I’m like, “No, they’re gone.” These were powerhouses when I was younger. The companies that do survive are ones who are able to adapt. The way they can adapt is because they have diverse voices speaking. I’m talking big diversity. I am talking certainly racial, gender, but socioeconomic, cognitive differences. I was just talking to someone at Ernst & Young who their job is to find workers with autism to come join the company. That’s fascinating. It’s funny, we have a common joke around here where we’re known for being the island of misfit toys at Second City. A lot of odd birds find their way here and are very successful. Often it will be like, “Is that person on the spectrum?” Like everyone is on the spectrum. I think we all are.

However, part of what you get when you welcome in those different voices and make them part of the ensemble is they throw you. They throw you in the best way because part of the thing that we have to fight as human beings is our existing patterns and the stories that we tell ourselves to make sense of the world. You need that to get up in the morning. I get that. We all need our beliefs; but the reality is the world is probably very different than how we’re perceiving it and it’s certainly very different than how other people are perceiving it.

The more you can step out of your own patterns, the more you can practice divergent thinking. That’s where innovation and creativity come from. That is not something that you wake up with. It’s something that you need to practice. That’s what improvisers do. They have to do it because they’re getting on the stage in front of people and making up the script. It’s almost like forced innovation. If you had to do that and be like, “This is incredibly uncomfortable,” and you might fail at it, the reason they don’t is because they practice.

This is the thing, I don’t know if you and I have talked about this Kelly, but how amazing is it that you never come to Second City and think that they didn’t or shouldn’t have rehearsed? You would never go to the ballpark and say, “Did this team not practice?” They don’t need to practice. You never go to the symphony and say, “No, they didn’t rehearse.” Yet, millions of dollars are on the line in business and how many of those people are practicing? Very few. They’re doing a ropes course maybe once a month or a year.

It’s so funny how we think it should just come naturally. We go through sales training and things like that but we often think our relationships in business, and certainly even our marriages, we just think I should just know how to do this. However, in reality it really is a practice. You probably remember this Kelly, our conversation at the summit dinner, and I know you’ve said this in some of your TED Talks that improv is like yoga for your social skills. Really, yoga is a practice. Everything we want to get really good at is a practice and it only looks easy because you do it every day.

It’s because this is what’s on the line. Second City is this corporate division. Second City works, that goes into tons of companies doing training, and someone legit, they didn’t really understand what we did, said, “Why would my company need you?” I said, “Do you have human beings who have to work with other human beings, because if that’s the case, then you need us.” I don’t know if you’ve noticed, it doesn’t go great. I don’t know if you turned on the radio this morning, not going great. Even in these weird times that we live in, it’s always been weird times. This is the dichotomy of course because the world’s never been more peaceful, there’s never been less disease, more education, more equality, less slavery, all these things are true in the world.

Be comfortable in supporting your people but challenge and make them uncomfortable.

Yet as Americans in 2018, waking up, if you put on any mainstream news source, it’s like everything’s on fire. This is a phrase that I found myself saying over and over and over again recently which is both things are true. That’s very hard for human beings to recognize. That yes, stuff is really difficult and stuff’s great. That’s the way it always is. If you’re in a business, you want to be very comfortable in supporting your people, in cheering them on, and at the same time you need to challenge them and you make them uncomfortable. Both things can be true.

Leadership Through Community: If you really care and you care so much, you don’t give the note because you don’t want to hurt their feelings. It’s called ruinous empathy.

Life is really a series of opposites. One of our speakers at the last summit gave us all these statistics about poverty and crime and lifespan. By the numbers, things are so much better right now. Our quality of life is so much higher yet we don’t always perceive it that way. One of the books that I was reading recently addressed this relationship between chaos and order and how they’re always switching places and one is following the other and returns around, and there’s always these opposing forces at work pretty much constantly; and because they’re always in flux, it can feel like one big improvisation. Pat, you have something to add?

In all the things that you said as you were unpacking that, one of the things that I took away was the idea of how you talked about it as a skill that is practiced, which the hopeful component of the idea of using the techniques of improvisation to be more yoga for your social skills. That it can be learned. That’s an exciting thing. The other thing that I took away from it is that as a leader, sometimes you have to challenge your people as well as be part of the ensemble. Sometimes you play the role of the audience as well as play the role of the player. How would you see as a director, being the role of the leader or the challenger, so to speak, versus the ensemble player that’s hoping to get as much from the team as possible?

I had a really stupid idea to create a Jewish themed musical that was called Jewsical the Musical. We really thought this thing was going to knock it out of the park. In fact, there was another person who stole the name and there was a legal fight, whatever. We’re at the Spertus Institute for Learning here in Chicago and they are allowing us to test some material out in front of audiences; and totally as a side thing like, “Would you maybe run a couple of workshops in?” Sure, whatever.

From Jackie’s leading the workshop, Hal Lewis, who was the director of the institute who’s an expert in Jewish leadership is watching the workshop, he pulls me aside he’s like, “Kelly, this is amazing.” I’m like, “Yes, it’s an improv. They’re cool.” He goes, “No, you’re doing Peter Drucker.” I’m like, “Who’s Peter Drucker?” He’s like, “You don’t know Peter?” “No, I’m a theater producer. I don’t know him.” He gives me a book and I go back and I start reading about this management guru and I recognize that indeed we have a concept and this was the exercise being done called Follow the Follower.

In Follow the Follower, one person is chosen to be leader of the group; and they, at some point, need to hand off leadership just through their eyes and to one person. That person needs to take leadership and then everyone else has to figure out who the new leader is. That’s it. That’s the superpower of if you’re able to turn and be like, “Your turn,” because when you think about it, when you’re improvising on stage, and I’m the one saying the words. Your job is to only listen to me. One of the problems is you can’t start formulating what you want to say because you really have to listen to me. This is the thing that we all don’t do in real life because we start formulating and stop listening. The last few words might be crucial so you have to take your time, and then when I hand it off, you’re in charge and then I’m suddenly not in charge.

This dynamic plays out among the ensemble.

This dynamic plays out among the ensemble. Our ensemble does have a director. The director is able, from the outside, to have their point of view and their job is to give notes. We have a phrase in our work which is called Take the Fucking Note. It doesn’t mean that you actually have to use the note, incorporate the note, whatever. The director is giving you their idea of how to improve your performance. If you’ve got a better way to improve your performance, believe me, no leader is going to be like, “Don’t do that. If you’ve got a better way, I’d rather you do it my way.”

By the way, if they want it their way, you’re probably in the wrong business or you’re working for a jerk. When you take the fucking note, just take it. Don’t fight it. Try to find what the note meant. My friend, Kim Scott, who’s got a great book called Radical Candor, has a wonderful way of talking about this feedback where you really want to give honest, radical candor and you can only do that if the person sitting across from you trusts that you care about them. The downside of this, if you really care and you care so much, you don’t give the note because you don’t want to hurt their feelings. She calls that ruinous empathy. Believe me, it is the worst thing.

I just have to ask you a follow-up question on this. It’s such a critical part of the conversation. We’ve been talking a lot about candor lately at work, and true to lots of organizations, we are seeking to always evolve our culture and make sure we’re working better as a team and it certainly involves our ability to have candor. Earlier we talked about our filters on the world. We’re all experiencing something different.

How do you manage the way in which people filter their feedback? We all do it. We all apply different meanings to what we think we hear when we’re getting feedback. We’ll be talking to someone and whatever experiences from our past are coming into play and we interpret it, no matter what the intentions, it may change. How do we think about overcoming these human barriers of defensiveness or just seeing the world in such a different way? How do we think about that?

This is where that elusive concept of culture comes in. As you point out quite rightly, we human beings are complicated and we’re often not going to hear even with the best of intentions. When you have a culture around you that can allow for a truth to be spoken to power and for people to be able to hear from their leaders uncomfortable things that won’t put them completely in their fear brain. Someone once said that we’ve been running on the Savanna longer than we’ve been running for the bus, we have to recognize the way we’re wired is to be in our fear brain.

This culture part, which it’s soft, it’s squishy, it’s often badly promoted and marketed. The reality is it isn’t soft, culture is hard. At Second City, when we are successful at this kind of stuff, it’s when we really are emulating this process that we’ve built into our creative work on stages. We’re not always successful. In fact, we’re more often not successful because we fail to translate it. I’ll give you an example of a place where we’re successful with it. Because here’s the deal, you can’t just have the lofty things, the statements, the ideas; you need to have at practical structures.

Two ideas come to mind that we have. One is the Second City Holiday Party. I’ve been at Second City for 30 years. This has been going on ever since I’ve been here. It was previous to that. Every year in the Second City’s Holiday Party, what happens is there’s a show that is put on by the staff and it’s a parody show. They take the scenes that are on stage now from the two or three reviews that have played during that year and they parody those scenes to make fun of both the actors and the bosses at the theater.

One year, a group of waitresses were parodying one of our songs from the show and it was all about the fact that they didn’t get insurance. One of the actresses ended up walking off the stage right in front of our owner, Andrew Alexander, and says, “You can dress up a pair of jeans. Why don’t I have insurance?” Mike Conway, the general manager, was sinking in a seat right next to him. The next day, Andrew called all of us into his office and said, “How do we get them insurance?” That would not have happened unless we have this mechanism. We’ve had executives who have been briefly with the company and there’s a reason they’ve been briefly with company. When they came and saw that show, and I remember sitting next to one of them, and she’s like, “This is terrible. How can you take what they’re saying about you?” I’m like, “What do you mean? It is an honor to be lampooned by them.” It’s completely honest and I can take it and they know I can take it.

I’ll give you another example, and this is speaking to the fear brain part, because culture is about creating scenarios and structures so that your people can apply their best selves. We know that people get into their fear brain. We know that they think in there in their regular patterns and we want to upset that. How do we do it? Mick Napier, who is a director here, does a thing, not always, but sometimes in this process, especially if he feels like he’s not getting interesting material and he calls a taboo day, your job is to bring in an idea for a scene that Second City would never put up on a stage. It’s too offensive. It’s too stupid. It’s too far out there. Invariably, half those scenes end up on the show. You think about this in a business context. Why don’t you have Terrible Idea Day for your company where everyone has to bring in an idea that should get them fired, but it is allowed to be put up on the board and played with. I’ll bet you, you’re going to find something.

That is such a growth space for organizations. I want to draw from a TED Talk you gave about failure because I love that talk. I wrote down one of the things that you said, I quote, “We need to mindfully linger in our mistakes.” You also mentioned falling in the crack of the game. It really takes courage to put yourself out there, whether it’s a taboo idea or just something that seems really out of bounds because no one wants to expose themselves to ridicule to damaging their career. It really goes back to that fear brain. Can you expand on the whole idea of just lingering there in this failure so that we can embrace the discomfort and find these golden things that may be hidden there?

We keep putting this on our people to be more innovative and yet the structures around them are keeping them from doing just that. This is where leaders and bosses come in. How do you create systematically spaces to fail forward? That is a thing. We do it in the context of this creative process that we’ve got, but I don’t want them failing on opening night. It’s not okay to fail an opening night. This is the thing you need to understand about failure is that there’s distance and time involved in all these other things. It’s not just like failure, bad failure, good; but it is like failure positive. You can think about this in terms of stress. We need stress. That’s not a bad thing. There are bad aspects of it. If you’re stressed out, stress is part of what makes you perform. We have all the cognitive dissonance around these words and these concepts and these ideas when our knowledge shows us better.

We’re going to get it wrong and that’s okay.

In a business sense, we have recognized is that we do need an ensemble that is elastic in the sense that they can poke holes, they can support, they can do all these different things at different times when we need them. We’re going to get it wrong and that’s okay. One of the problems about the world we live in right now, and this is business and culture in America and all of that, is we’re no longer allowing ourselves to stay inside difficult conversations. We have decided that our bubbles and our jerseys and all of that is how we’re going to approach the world. We’re more interested in shaming each other than teaching each other. We do a lot of D&I training. I don’t know if you’ve seen the data on this. It doesn’t work, far and away.

The Diversity Inclusion Training has zero success rate. There’s almost no data to support that it’s effective. Part of the reason is people go in so scared and so defensive, and of course, they do. Our D&I training is not about trying to get you to not say the wrong thing because you’re going to say the wrong thing because what was the right thing three days ago is suddenly the wrong thing now, or three weeks, or three months, or three years, or three decades. However, what we do when we go in is give you the skills and agility to respond when the wrong thing gets said. That’s for everyone.

Radical Candor: Be a Kick-Ass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity

Kim Scott, who I bring up, we’re working on a project together around gender conversations with Radical Candor and the idea here is recognize that this conversation that we’re having in our business, involves a person who’s offended, the person who did the offending, and the person who witnessed it or didn’t. That’s the ensemble we need to be playing with all of them. How do I give you agency to tell me that you’ve offended me? How do I give myself agency to say I’m sorry or find the way to stay on the side of the conversation? Most of all, it’s really not mostly about us. It’s about the person on the outside being able to come and go, “I just saw this. I don’t think this is cool. Let’s talk about it,” and give ourselves the opportunity to grow together. All of us.

We definitely tell stories with humor and the more you talk about the science behind the comedy, the more I realize that maybe we’re thinking about it only as art and we’re looking for that way to be funny or sarcastic or hit some catchphrase with our consumers. Perhaps, going back to our conversation about how many things in life for our practice there’s an opportunity for all of us to be more deliberate in our intention about what we do and what we say and how we say it so that we’re really resonating in the right way with our customers and with our consumers. With social media, we get into direct conversations with them so it’s really important that we are understanding this and really doing a better job as we evolve our brands into the future.

What I’m hearing in this, when you think about chaos and order and the power of the ensemble and being able to have conversations where good and bad feedback are taken, is that the underpinning for success in all things is a mutual trust. Going back to the hopeful statement before is it seems that it can be learned.

I’d be interested in your point of view on how you are able to instill and teach that skill of mutual trust that empowers the success that you talk about because what I heard at the very beginning of this statement is that you’re successful because you fail. You’re able to fail because you have trust in the feedback and you’re able to get the meaning behind the note. If you could talk a little bit about that, that’d be awesome.

Here’s the first thing: it’s okay to fake it till you make it. That is absolutely the first thing. A friend of mine who’s a Harvard professor, this is when I first started doing speaking dates, at a conference, I said I get nervous before these and she laughed. She’s like, “How do you get nervous?” I go, “I do.” She goes, “You need to say you’re excited and you need to say that out loud. Don’t ever say you’re nervous before speech. Literally say you’re excited.” I tried it and it worked and then she said to me, “Yes, I wrote a paper on it.” Literally, I’ve got data around the fact that if you simply say those words, you’re helping yourself.

Part of the reason businesses bring us in is because, specifically, we make you actually say words. We make you look people in the eye. We make you do these things that you really don’t want to do probably or you’re afraid but you have to be at the thing. After you do them just like a workout, you’re like, “I really should do this every day,” and you’re not going to. This is where the practice part comes in. You need to instill. I’m not saying like forced workshops, but I’m certainly saying some level of ordained practices inside a company that allow your people to practice their communication skills, practice their collaboration skills, all that stuff we talked about.

If it’s not improv, there are other things that can do it. It’s so important because just as we’ve seen the power of connection, we all understand that just because you have it today doesn’t mean you’re going to have it tomorrow. In fact, you usually don’t. It doesn’t sustain itself just like magic. You’re going to lose it. That’s why all these great companies we talked about earlier that are gone, in part, I think the big reason and lesson is history repeats itself. We see it over and over again. They just stopped seeing what was in front of them.

I joke often that I’ve literally driven the same way to work for 30 years. This is not a lie. This is where I’ve lived my entire adult life in Chicago, working at The Second City. Second City hasn’t moved since that time. I’ve moved, but I’ve always taken the Lincoln. I no longer see the route until I blew myself up at Second City and stepped down from running it. It was when they gave me the great honor of sticking around for a year to try to figure it out that I started seeing what it looked like. I remember this is true and just an impersonal way too. When I met my wife, Ann, and I was coming out of a marriage that broke up, I’d often say it was like the time I first got glasses and I could see definition on trees. It was like, “I didn’t know who it could be like this.” I think at work when we have our successes, we often feel very similar human feeling but it doesn’t just stay.

The crucial thing, and I think it’s called expert syndrome but there might be another term for it, but it’s this idea that as we become more successful, we are more likely to not have success in the sense that we’ll have our position of power and that gap gets maintained, that’s great. However, we’re not happier and we’re not inventing as much because it’s always worked this way for us so we keep doing it the same way and then all the conditions change. I’m in the comedy business here. Let’s talk about the world we live in right now. It’s different so you can’t say things that we used to say. Our audience is showing us this and if we can’t respond in a moment to be like, “Check it. Can’t say that,” we’re dead in the water. We are a dead institution. That is such a gift because we are, in the moment, in smaller groups and most businesses don’t have that luxury. They find it out when someone sends a bad tweet.

Actually, I want to ask you because to your point, over almost 60 years that Second City has been here and only in the last maybe ten, has the ability to react to something that you do on stage and broadcast to the masses instantly could happen. You could say something on stage and if there’s a Tribune writer or Sun-Times writer in there, you might get it the day later, you’re ready to react to it. You could walk off-stage and the world is blowing up. How has that impacted the way you go about what you do and how have you managed through it? I’m sure you’ve probably had times when it’s tough.

We’re still lucky in that an audience member sitting inside a live theater where there’s maybe 300 or 1,000 people from the road has less social power as opposed to a person who’s using the medium of say Twitter or Instagram or Facebook or whatever to do their work. They’re now playing to millions and millions and millions directly. To jump on that is where people get into real trouble. We have yet to get into real trouble. We’ll have people troll us or take something out of context, but I have found that mostly comes and goes pretty quickly. That’s the benefit of being in our medium. I happen to be married to a comedy professor. She runs the first BA in Comedy Writing and Performance ever in the country at Columbia College here in Chicago, four-year degree. As she says, she’s every parent’s worst nightmare. However, what those kids learn is there’s science behind this comedy stuff and they learn that the context changes the meaning of your comedy, and that when you are doing physical comedy, that is different than your point of view comedy which is different than narrative.

Let me put it in these terms, so many people in marketing are using comedy without a license. They use comedy to communicate their messages because it’s so sticky and what do they know about comedy? They haven’t studied it. They’ve watched Seinfeld. Maybe people say they’re funny. The reality is, Ann and I and the people who work at Second City have dedicated our lives to understanding not just like what is funny or who is funny, but how it gets made. I’ve seen directors where a joke isn’t getting a laugh and you just have to cheat out to the audience like two inches and then suddenly it gets a laugh. I’m like, “What is that?” There’s actually science around what that is. If you are armed with the ability to really understand how to connect with humor, we’ve seen how that ad is working. In these times of trouble, who are we looking to? We’re looking to John Oliver, Stephen Colbert, Seth Meyers, looking at Sam B. There are truth tellers now. It’s not Walter Cronkite. It’s Trevor Noah. It’s people who are showing us from the outside a vision or an idea of the world that they might see and that’s allowing us to laugh instead of cry. I don’t know what the percentages of advertising, but how much of that is comedy? How much of that is using humor?

I heard this somewhere. It may have been in an improv class. Someone said at one point if you trip and fall in front of people, you just get up with confidence and say, “Ta-dah,” like you meant to do it. I think that’s probably a good strategy if you need to get through something like that. I can’t believe that we are at a time. I feel like I could talk to you for like five hours. There’s so much good information here, but I do want to close out the podcast with one question.

I’m going to focus in on your journey. 30 years at the Second City and you co-wrote a book called Yes, And where you do a deep dive into that concept and how it is applicable in so many domains. You also launched your podcast, Getting to Yes, And, to have more conversations around that. I’ll tell you something, Kelly. You may have taken the same route to work all this time, but you definitely have evolved and changed.

You’ve continued to reinvent yourself over and over. I also know that you are continuing with outside collaborations that are producing some really amazing new ideas and thinking. As we return to the community thread and the power of co-creating things together, share with us as you think about your journey, why is it so important that we do all this together that we connect in new ways so that we find out how this connection’s really going to evolve us and make us new and different?

I’m interested, actually. You said something that piqued my interest relative to the business that you’re in, the industry that you’re in, and the industry that we and many of our listeners are in. In terms of, so many startups, so many people that don’t have the license to do comedy within the context. Have you ever found yourself inspired by someone who has no training but somehow or another made it into the commercial world? Because for a lot of big industries and big companies, it’s the little guys that are really bringing some of the new and different things. I’m just interested in your point of view on that.

Yes, we have a system by which that all we’re dealing with is the little guy. Here’s the reality too. There’s no such thing as a natural. There are people who are very, very funny and through learning and educational programs and practice and all that become incredibly successful. My wife’s working on new book. Her book is called Funnier, and someone’s like, “What does the title mean?” People always ask her can she make people funny. She says, “No, but I can make them funnier,” because some people are not funny at all. She’ll make them a smidge funnier but they’re not going to be hired by Second City. If you’re like Amy Poehler and other people that she taught, we’re like, “Yes.” They came in and they were killer. They still needed to practice and hone their skills, they’ll tell you and fail a lot to get better.

The disruptors that we see in our world that I get a little jealous of are the people who so don’t fit my idea or our idea of Second City that we look past them and only later that we realized they could have changed what we do for the better. That does happen because I have, and we all do, our idea of what a Second City person is. There’s a very gifted comic performer named Conner O’Malley who’s based in New York. He dates Aidy Bryant. Aidy came out of Ann’s comedy program at Columbia and she’s on Saturday Night Live right now. She and Amy Schumer hosted a screening of their new movie for all female students of the Second City and is so cool. Connor is out of the mind like I never knew what to do with him and he has now gone on and made incredible success of himself. I look at that and that’s repeated itself over time so much so that even though I’m not doing the casting anymore, it’s something I really try to remember, to figure out if they are special, a way to make it work.

Here’s another person I let go, Kumail Nanjiani. I remember seeing Kumail at the Lincoln Lodge. There’s this Lincoln diner that had a back room and all these great comedians who are all famous now were playing there. This night, no one was good but Kumail was amazing. I had a conversation with him and I wasn’t smart enough, I was like, “He’s a stand-up. We don’t do stand-up.” It’s like, “No. Find a way to get this voice in because it’s so brilliant,” and of course, gone onto great things.

Thank you for that because your answer actually got where I was trying to go with my question, which was it also links back to what you said. It’s like you’re learning from the misses too. You don’t learn from the successes.

In comedy, a success story is not funny.

This is the other thing in comedy, a success story is not funny. That’s just you bragging. You know what the funniest stories are? There’s a fantastic This American Life episode which I think is called Fiasco! It is the best stories. It is just everything goes wrong in these situations and you realize that’s really the thing. That’s what we’re responding to. I would imagine, biologically speaking, that that’s how we’re protecting ourselves. We’re using humor as a way to let ourselves off the hook for our failures.

Leadership Through Community: When you are doing physical comedy, it is different than your point of view comedy which is different than narrative.

You said in one of your TED Talks that one of the learnings that you received over time was that in all these interactions you had with people that 99% of all of us out there feel like we’re a fraud. It’s so interesting. We think about our own ability to have power and agency and impact no matter where we’re coming from. We’ve talked a lot in this conversation about humanity and the importance of that in the workplace and the beautiful opportunity that we have to come together and really create something different. Let’s face it, we all do experience our worlds in such different ways and when we bring that to the table and push our edge and trust each other that we’re trying to make each other better, so many amazing things can happen. When we change our dialogue from being nervous and scared and afraid to excited, it is so much more fun.

Surround yourself with people who are going to challenge you but love you.

I think I know the answer, but I don’t know necessarily how I was able to get there. The answer is you need to be open to how wrong you are and have people tell you that and push you in ways that you don’t want to be pushed. When I look back at my wife, Ann, to Andrew Alexander, our owner, to colleagues and actors like Kevin Dorff. He’s an actor and brilliant improvisor. I believe he was part of a group who kidnapped me in order to force me to hire X number of people to change the trajectory of the theater and I allowed myself to be influenced in that. I think that the key to that is surrounding yourself with people who are going to challenge you but love you.

If you don’t have that, the two don’t work. If you don’t have the love, you’re not really going to feel safe or do the challenge and you’re not really going to be challenged by people who don’t love you. Allowing that level of vulnerability and authenticity to exist, it’s scary. It’s not great all the time. You have real dark moments with regard to it, but it feels to me, looking back over the course of my career, that every time I allow myself to be challenged, and it’s those same people over and over again who have done it, I’ve been able to serve. I’m still here. I still drive the same way to work but I’ve nudged myself in a certain direction to not be afraid to try something completely new. There’s a foolish fearlessness that sometimes you just have to play with.

What I’ve been doing, and we talked about this before, is I’ve been trying to book people on the podcast I’m scared to talk to. They are either so progressive as to intimidate me. I want to have Danny Kahneman on who I think is the smartest person in the world. That’s the one that I haven’t pulled the trigger on because I’m so scared of talking to someone that’s smart. There’s a guy coming on, his book’s over here, Leonard Mlodinow. He was booked on the podcast and he couldn’t come because he had to go to Stephen Hawking’s funeral because he co-wrote books with him. He’s a physicist and the book is called Elastic. He talks about the neurology and science behind what he calls elastic thinking. I understood a good percentage of it, but not all of it.

It’s intimidating to me, but what I recognize is he is a human being who is probably coming on the podcast going, “I’m afraid this guy’s going to be funny. It’s The Second City podcast.” All I’m thinking about of his power and I’m forgetting that I have agency, empower myself, and that collectively, putting those two things together might create incredible discovery because that’s usually what ends up happening. It allows you to work at those edges of your network and allows you to, that phrase that we’ve got, where you fall into the crack in the game. You find the scariest little place and you jump in and see what happens. A major discovery, a huge success, an incredible product launch that probably didn’t seem insane when someone first brought it up.

Kelly, as we close out this conversation, I just have to tell you it has been so engaging and we are very grateful for your time, for hosting us here, and sharing so much wisdom. We might need a part two. There is so much to talk about with you. It’s phenomenal and we just appreciate so much your partnership and collaboration with the CMO Summit community so thank you again for everything that you do and all that you are. Thanks for helping us launch our podcast.

About Kelly Leonard

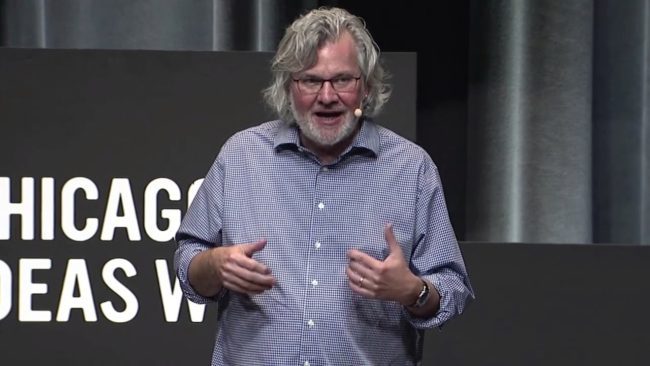

Kelly Leonard is the Executive Director of Insights and Applied Improvisation at The Second City and Second City Works. His book, “Yes, And: Lessons from The Second City” was released to critical acclaim in 2015 by HarperCollins and was praised by Michael Lewis in Vanity Fair who called it “…an excellent guide to the lessons that have bubbled up in Second City’s improv workshops.” Kelly is a popular speaker on the power of improvisation to transform people’s lives. He has presented at The Aspen Ideas Festival, The Code Conference,TEDx Broadway, Chicago Ideas Festival, The Stanford Graduate School of Business and for companies such as Coca Cola, Microsoft, Memorial Sloan Kettering and DDB Worldwide. Kelly co-created and co-directs a new initiative with the Center for Decision Research at the Booth School at the University of Chicago, The Second Science Project, that looks at behavioral science through the lens of improvisation. He also hosts the podcast, “Getting to Yes, And,” for Second City Works and WGN radio that features interviews with thought leaders such as Simon Sinek, Adam Grant, Gretchen Rubin, Dan Pink and Brene Brown.

For over twenty years, Kelly oversaw Second City’s live theatrical divisions where he helped generate original productions with such talent as Tina Fey, Stephen Colbert, Amy Poehler, Seth Meyers, Steve Carell, Keegan Michael Key, Amy Sedaris and others. He lives in Chicago with his wife, Anne Libera and their children Nick and Nora.

Twitter: KLsecondcity

Important Links:

- Second City

- Caring Across Generations

- Dr. Samuel Wells

- Radical Candor

- Andrew Alexander

- Mike Conway

- Yes, And

- Getting to Yes, And – podcast

- Kumail Nanjiani

- ElasticLove the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Join The Coca-Cola CMO Leadership Summit Podcast community today:

Cultivating Leadership Through Community, Cultivating Leadership Through Community with Kelly Leonard, Kelly Leonard, Leadership Through Community